Modern applications rarely operate as single, self-contained programs. Most rely on dozens of services, APIs, and cloud components that must exchange data quickly and reliably. As systems grow more complex, middleware becomes the quiet layer that keeps communication organized and predictable.

When no proper integration layer is in place, small issues tend to multiply. One service may change its data format. Another may respond slower than expected. Suddenly, developers spend more time fixing connections than building features. Integration challenges become even sharper inside distributed systems where components run across multiple environments.

At its core, the problem is simple. Applications need a reliable way to talk to each other without creating fragile, hard-to-maintain links. That is where an intermediate computer software layer steps in. It handles routing, translation, and coordination so each service can focus on its own job.

Developers early in their journey often find the topic intimidating. Complexity often looks worse than reality. With the right mental model, the role of the integration layer becomes clear and practical. The sections ahead break down how the technology works, where it fits in modern architecture, and why it continues to power scalable software platforms across cloud and on-premise environments.

What Is Middleware

Simple Definition

Middleware is software that sits between applications and systems, managing communication, data exchange, and coordination so different components can work as one cohesive solution.

In simple terms, think of it as a smart connector. Applications often speak different “languages” or follow different protocols. A dedicated software layer translates, routes, and manages interactions so developers do not have to build custom glue code every time systems need to talk.

According to IBM, middleware is software that enables communication between applications or components across distributed systems.

Put plainly, the technology acts like a traffic controller for software. Instead of each application handling complex connection logic on its own, the integration layer centralizes the heavy lifting. That shift reduces development time, improves reliability, and makes large systems easier to maintain as they grow.

Where Middleware Sits in System Architecture

Inside a typical stack, the middleware layer lives between the application layer and the operating system or backend services. The component does not replace either side. Its job is coordination.

Picture a web app sending a request to a database. The application issues the request, the integration layer validates and routes it, and the backend service returns the result. During the request/response cycle, the middle layer may handle authentication, data formatting, and routing decisions before the response travels back to the user interface.

Quick Real-World Analogy

Imagine ordering food through a restaurant waiter. A customer does not walk into the kitchen and speak directly to the chef. The waiter takes the request, ensures clarity, delivers it properly, and brings the finished dish back.

That behavior mirrors how an integration layer operates in modern applications. The software layer stands between components, ensuring messages arrive correctly while each side stays focused on its primary responsibility.

Why Middleware Matters in Modern Systems

As applications expand across cloud platforms and microservices, integration challenges multiply quickly. Direct connections between every component create brittle systems that are difficult to scale or troubleshoot. A centralized integration layer reduces friction by standardizing communication logic and simplifying service interactions.

According to Microsoft Azure, the middleware layer acts as software that helps applications, systems, and services communicate and work together efficiently.

In practical terms, the layer removes repetitive plumbing work from individual services. Developers can focus on business logic while the integration layer handles routing, security checks, and message coordination. The separation becomes critical in distributed environments where services may be written in different languages or deployed across multiple regions.

Scalability pressure also plays a role. As user demand increases, systems must process more requests without breaking. A well-designed middleware architecture helps balance loads, manage queues, and maintain consistent communication patterns. The result is a system that grows more gracefully and remains easier to operate under real production stress.

For teams building modern platforms, the technology is no longer optional. The integration backbone allows complex services to function as a unified, dependable application.

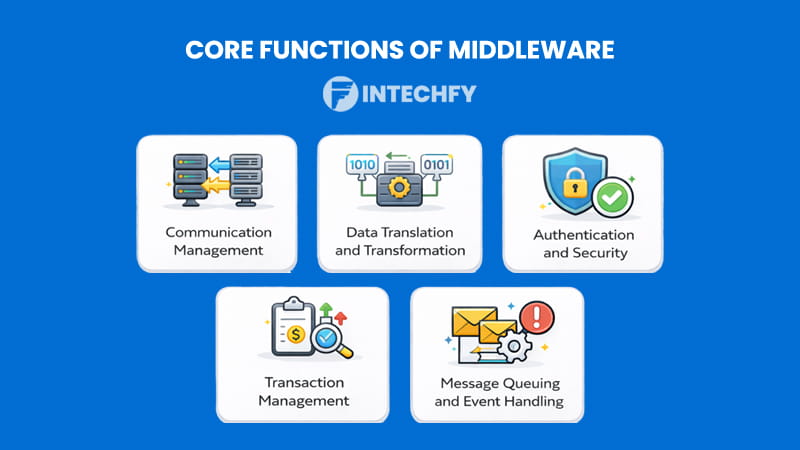

Core Functions of Middleware

Modern software rarely operates in isolation. Applications talk to databases, external services, and cloud platforms constantly. Middleware handles the operational work that keeps those conversations reliable and organized. Instead of embedding communication logic inside every service, teams place coordination responsibilities in a dedicated layer.

At a practical level, the technology manages routing, security checks, data shaping, and transaction safety. Developers gain cleaner codebases and fewer fragile connections. Systems also become easier to scale since communication rules live in one place instead of being scattered across many services.

In distributed environments, the operational role becomes even more valuable. Services may run in different regions or use different programming stacks. A well-designed middleware architecture ensures consistent behavior even when underlying components evolve independently. The following functions explain how the layer keeps complex platforms running smoothly.

Communication Management

One of the primary responsibilities involves request routing and service coordination. When an application sends a request, the integration layer decides where the message should go and how it should travel. Proper routing prevents bottlenecks and avoids hard-coded service dependencies.

Many teams implement an API gateway at this stage. The gateway acts as the front door for incoming traffic, enforcing routing rules and balancing loads across services. With centralized communication management in place, systems remain flexible even as new services are added or existing ones change location.

Data Translation and Transformation

Applications rarely store or transmit data in identical formats. One service may use JSON, another relies on XML, and a legacy system might expect a custom structure. The software bridge performs format conversion so each component receives data in the structure it expects.

Interoperability improves dramatically when data mapping happens automatically. Instead of forcing every team to align on one rigid schema, the integration layer reshapes payloads on the fly. For example, an e-commerce platform can accept mobile app requests in JSON and convert them for a backend inventory system without manual intervention.

Authentication and Security

Security enforcement often sits inside the middleware layer. Identity handling begins when incoming requests arrive with credentials such as API keys or OAuth tokens. The layer validates those credentials before any backend service processes the request.

Access control rules also live here. The system checks permissions, enforces rate limits, and blocks suspicious traffic patterns. Token validation ensures only authorized clients reach sensitive services. Centralizing security logic reduces duplication and lowers the risk of inconsistent protection across different parts of the platform.

Transaction Management

Reliable systems must maintain consistency even when failures occur. Transaction management ensures multi-step operations either complete fully or roll back safely. The middleware component tracks transaction state and coordinates commits across services.

Consider an online payment workflow. Funds should not be captured if inventory reservation fails. The transaction manager monitors each step and triggers rollback procedures when something breaks. Reliability improves since partial updates no longer leave data in an inconsistent state.

Message Queuing and Event Handling

Modern architectures often rely on asynchronous communication. Instead of waiting for immediate responses, services publish events and continue processing. Message queuing inside the integration layer enables that pattern.

Event-driven architecture becomes possible when a message broker buffers traffic between producers and consumers. Systems such as Kafka or RabbitMQ allow services to process workloads independently without tight coupling. The result is better fault tolerance and smoother scaling under heavy load.

Key Characteristics of Middleware

Beyond individual functions, several defining traits make middleware software effective in complex environments. Those characteristics explain why the layer remains central to modern system design.

Interoperability

Interoperability means different systems can communicate even when built with different technologies. The integration layer translates protocols and data formats automatically. That capability matters when organizations run a mix of legacy and modern services.

For example, a Java-based backend can exchange data with a Node.js microservice without custom adapters in each application. The coordination layer handles the differences behind the scenes.

Scalability

Scalability reflects how well a system handles growth in traffic or workload. A properly designed communication layer distributes requests, balances loads, and manages queues.

Imagine an online store during a flash sale. Traffic spikes sharply. With centralized coordination in place, incoming requests spread across multiple service instances instead of overwhelming a single endpoint. Performance remains stable even under pressure.

Platform Independence

Platform independence allows applications running on different operating systems or cloud providers to work together. The integration layer abstracts environment differences.

For instance, one service may run on Linux containers while another lives on a Windows server. Communication still flows smoothly since the coordinating software standardizes the interaction model.

Transparency

Transparency means developers do not need to worry about internal communication mechanics. The middleware layer handles routing, retries, and formatting automatically.

As an example, a developer calling a user profile service simply sends a request. Behind the scenes, the integration component may perform load balancing and protocol conversion without exposing that complexity to the application code.

Reusability

Reusability allows common communication logic to serve many applications. Instead of rebuilding security checks or routing rules repeatedly, teams implement them once inside the integration layer.

A company running multiple microservices can reuse the same authentication pipeline across all services. Maintenance becomes easier, and behavior stays consistent across the platform.

How Middleware Works

A closer look at the request flow shows why middleware continues to play a critical role in distributed systems. Each interaction moves through a clear sequence, starting from the client request and ending when the response returns in a consistent format.

Middleware Request Flow

| Step | Actor | What Happens | Purpose | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Client/Application | Request sent to middleware layer | Start communication | Incoming request |

| 2 | Middleware | Validates request | Ensure security | Validated request |

| 3 | Middleware | Routes/transforms data | Match target service | Processed request |

| 4 | Backend Service | Processes logic | Execute task | Service response |

| 5 | Middleware | Formats response | Maintain consistency | Formatted response |

| 6 | Client/Application | Receives result | Complete cycle | Final response |

The table outlines a simplified request lifecycle. In production environments, additional steps may appear, such as caching, rate limiting, or retry logic. Even so, the core pattern remains consistent across most implementations.

Basic Request Flow

The interaction usually follows a numbered sequence:

- A client application sends a request toward the integration layer.

- Security checks validate identity and permissions.

- Routing logic determines the correct backend destination.

- The target service executes business logic.

- Response formatting ensures consistent output.

- Results return to the original client.

Each step isolates responsibilities. Services focus on core logic while the coordination layer manages communication overhead. The separation keeps architectures cleaner and easier to scale.

Example Scenario: Web Request Through Middleware

Consider a mobile app fetching user account data. The app sends an HTTPS request to an API gateway. The gateway forwards the call through middleware, which verifies the access token and checks rate limits.

Next, routing rules direct the request to the correct user service. The backend retrieves data from the database and sends a response back through the same path. Before returning the payload, the integration layer formats the response into a consistent JSON structure.

From the user’s perspective, the process feels instant. Behind the scenes, several coordination steps ensure reliability and security.

Why This Flow Matters

Clear request flow improves troubleshooting and scalability. Engineers can pinpoint failures faster since responsibilities are well separated. Load balancing and queue management also become easier to implement.

As systems grow, the structured communication model prevents tight coupling and reduces the risk of cascading failures across services.

Middleware Architecture Explained

Modern applications almost never depend on a single communication style anymore. One service might push events, another expects synchronous calls, and a third runs in the cloud with its own rules. Without a coordination layer, the whole setup becomes fragile very quickly. A service intermediary steps in as the traffic controller that keeps moving parts aligned.

A solid integration-layer architecture keeps services loosely connected while still allowing fast communication. Instead of hard-coded links everywhere, requests flow through a controlled middle layer that handles routing, transformation, and policy enforcement. The result is easier scaling and fewer surprises in production.

Architecture decisions matter more than many teams expect. A flexible design allows new services to plug in with minimal friction. Poor structure, on the other hand, turns every small change into a risky deployment.

Layered Architecture Overview

Most modern integration architecture follows a simple layered model. Client applications sit at the top. Backend services live at the bottom. The coordination layer operates in the middle and manages the conversation.

Many enterprise systems introduce an enterprise service bus to control message flow. The bus handles routing rules, protocol translation, and sometimes basic orchestration. An application server usually runs alongside it, hosting business logic while the middle layer focuses purely on communication discipline.

Middleware in Three-Tier Architecture

Classic three-tier systems separate responsibilities into presentation, logic, and data layers. The presentation layer handles user interaction. The logic layer processes business rules. The data layer manages storage.

In many deployments, the communication bridge sits between the logic and data tiers. A web application may trigger business logic first, then rely on the integration layer to safely reach the database. The separation reduces tight coupling and makes the stack easier to evolve.

Middleware in Microservices Architecture

Microservices change the game by splitting applications into many small services. Coordination becomes the hard part. The integration layer often works side by side with an API gateway that filters and routes incoming traffic.

Event streaming also becomes common. Services publish events and move on without waiting. A well-planned service coordination platform supports that asynchronous flow, helping teams scale individual services without destabilizing the wider platform.

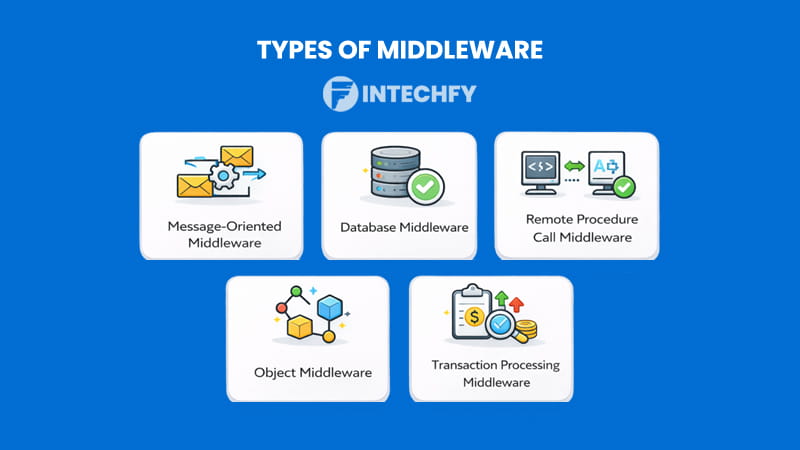

Types of Middleware

Not every system needs the same communication strategy. Some workloads depend on fast synchronous calls. Others work better with queued messages or distributed objects. Different integration solutions exist to match those needs.

Choosing the right category early can prevent painful refactors later. The sections below cover the most common types used in modern distributed environments.

Message-Oriented Middleware

Message-oriented messaging layer focuses on asynchronous communication between services. Instead of waiting for an immediate reply, applications send messages to a queue where consumers process them independently.

This approach works well in high-traffic environments where reliability matters more than instant response. A common use case appears in order processing systems. An e-commerce platform can place orders into a queue, allowing payment, inventory, and shipping services to handle tasks at their own pace without blocking the user experience.

Database Middleware

The database access layer acts as a bridge between applications and data storage systems. It manages connection pooling, query routing, and sometimes data caching to improve performance.

Teams typically use this type when multiple applications must access the same database environment. For example, a reporting dashboard and a transactional system may share customer records. The database integration layer ensures efficient connections and consistent access patterns without overloading the database server.

Remote Procedure Call Middleware

Remote Procedure Call (RPC) service invocation layer allows one application to execute functions on another system as if the call were local. Network complexity stays hidden behind a simple function interface.

RPC solutions are useful when low-latency communication is required between tightly coordinated services. A real-world example appears in internal microservice communication where services exchange small, frequent requests that must complete quickly.

Object Middleware

The distributed object layer supports communication using structured business objects. Instead of sending raw messages, systems exchange data structures that represent real entities.

The model fits enterprise environments built with object-oriented design principles. For instance, a financial platform might pass account objects between services for processing. The object transport layer handles serialization and delivery so developers can work with familiar structures.

Transaction Processing Middleware

The transaction coordination layer focuses on maintaining consistency across multi-step operations. Complex workflows either complete fully or roll back safely when errors occur.

Financial systems often depend on the model. Consider a banking transfer involving balance checks, debit operations, and credit updates. The transaction manager coordinates every step, guaranteeing data integrity even if part of the process fails midway.

Real-World Middleware Examples

Real production systems rely on proven tools to handle integration at scale. Several platforms appear repeatedly across modern architectures.

Common middleware examples include:

- Apache Kafka — built for high-throughput event streaming and real-time data pipelines

- RabbitMQ — popular message broker for reliable queue-based workloads

- IBM MQ — enterprise messaging platform with strong delivery guarantees

- NGINX — widely used for reverse proxying, load balancing, and gateway control

- AWS services (SQS, SNS, EventBridge) — managed cloud tools for scalable messaging and event routing

Each tool solves a slightly different problem. Kafka shines in event streaming. RabbitMQ handles traditional queues well. IBM MQ focuses on enterprise reliability. NGINX often manages traffic at the edge. AWS services remove much of the infrastructure burden in cloud environments.

Middleware in Modern Architectures

Modern software platforms rarely operate inside a single runtime or server boundary. Systems now span containers, regions, and even multiple cloud providers. In that environment, the integration layer becomes the coordination point that keeps services talking reliably without hard-coding every connection.

Middleware in Distributed Systems

Distributed systems spread components across different machines and networks. Latency, partial failures, and inconsistent data formats quickly become real problems. An integration layer helps normalize communication so services behave predictably even when deployed far apart.

In real deployments, engineers rely on the communication layer to manage retries, routing rules, and message formatting. Without that support, each service would need custom logic for network failures and protocol differences. The result would be brittle code and slower development cycles.

Large-scale platforms such as streaming services or payment gateways depend heavily on this approach. The coordination layer keeps nodes loosely coupled while still allowing high-throughput communication across regions.

Middleware in Microservices

Microservices architectures break applications into many small services. That design improves flexibility but introduces coordination complexity. The integration layer often works alongside an API gateway to manage incoming traffic and service discovery.

In production environments, service-to-service communication can grow chaotic without a central coordination point. A well-placed service intermediary handles request routing, circuit breaking, and sometimes rate limiting. Teams gain cleaner service boundaries and fewer cascading failures.

Event-driven patterns also benefit. When services publish events instead of calling each other directly, the messaging layer ensures events reach the right consumers without tight coupling.

Middleware in Cloud Computing

Cloud-native platforms introduce dynamic scaling, ephemeral containers, and multi-region deployments. Communication paths change frequently as instances spin up and down. The integration platform helps stabilize interactions in that constantly shifting environment.

Managed cloud services often include built-in integration features such as queues, event buses, and API management layers. Teams still need a clear architectural strategy, since poor coordination can lead to hidden bottlenecks. When implemented carefully, the middle layer helps maintain consistency across hybrid and multi-cloud systems.

Benefits of Using Middleware

Organizations adopt the coordination layer to simplify communication, improve resilience, and support long-term scalability. The advantages become more visible as systems grow in size and complexity.

Key benefits include:

- Simplified integration: Services communicate through a shared coordination layer instead of building custom connectors for every pair of applications.

- Improved scalability: Load balancing and queue management help systems handle traffic spikes more smoothly during peak usage periods.

- Stronger security controls: Centralized authentication and access policies reduce the risk of inconsistent protection across services.

- Better fault isolation: Failures in one service are less likely to cascade when communication passes through a managed intermediary.

- Faster development cycles: Teams can focus on business logic instead of low-level networking concerns.

In many enterprise environments, organizations report integration effort dropping by 30–50% after introducing a well-designed integration backbone. The exact number varies, yet the productivity gains are often significant.

Another advantage appears in long-term maintenance. A consistent communication backbone reduces technical debt and makes platform evolution far less painful.

Middleware vs Similar Technologies

Confusion often arises when teams compare the integration layer with APIs or message brokers. Each technology plays a different role in system design, even though they sometimes appear in the same architecture.

An API defines how clients interact with a service. A message broker handles asynchronous message delivery. The coordination layer operates at a broader level, managing routing, transformation, and policy enforcement across multiple services.

Middleware vs API vs Message Broker

| Technology | Primary Purpose | Scope | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Middleware | Integration layer | Broad | Complex systems |

| API | Interface contract | Narrow | Direct service access |

| Message Broker | Async messaging | Event systems | Decoupled services |

The comparison highlights how responsibilities differ. APIs focus on exposing functionality. Message brokers specialize in queue-based delivery. The service coordination layer provides the glue that keeps multiple interaction patterns working smoothly inside distributed environments.

In real deployments, the three often work side by side. A typical cloud platform may expose REST APIs at the edge, use a message broker for background processing, and rely on the integration platform to enforce routing, security, and transformation policies. Treating them as interchangeable tools usually leads to architectural confusion.

Key Takeaways from the Comparison

Choosing the right tool depends on the communication problem being solved. Use an API when a client needs direct access to a service endpoint. Choose a message broker when asynchronous event flow is the priority.

Reach for the communication backbone when coordination spans multiple services, protocols, or environments. The approach shines in complex systems where routing, security, and data transformation must remain consistent across many moving parts.

Teams designing modern platforms often combine all three approaches. The key is understanding the scope of each tool and avoiding the temptation to force one component to solve every integration challenge.

When You Should Use Middleware

Not every application requires a full integration layer. Smaller systems with only a few services may function perfectly well with direct API calls. Even so, certain warning signs indicate when the service coordination layer becomes the safer architectural choice.

Signs You Need Middleware

Use the checklist below as a quick reality check:

- Multiple services communicate across different environments

- Data formats frequently require transformation

- Security rules must be enforced consistently

- Traffic spikes create reliability concerns

- Event-driven workflows are expanding

- Service dependencies are becoming hard to manage

If several items apply, introducing a dedicated integration layer usually improves long-term stability and maintainability.

When Middleware May Be Overkill

For small applications with simple request flows, adding a full coordination layer can introduce unnecessary complexity. Extra infrastructure means more configuration, monitoring, and operational overhead.

A lightweight API-based approach often works better when:

- the system has only a few tightly related services

- traffic volume is predictable and low

- data transformation needs are minimal

Architecture should match real complexity. A full integration platform delivers strong value at scale, yet thoughtful teams avoid deploying it where simpler patterns already meet the requirements.

Common Misconceptions About Middleware

Misunderstandings still surround middleware, especially among teams new to distributed design. Many developers either overestimate its complexity or underestimate its role in modern platforms. Clearing up a few persistent myths helps teams make smarter architectural decisions.

Middleware vs API Confusion

One of the most common mix-ups involves APIs. An API defines how one system exposes functionality to another. The integration layer operates at a broader level, handling routing, transformation, and cross-service coordination.

In real deployments, both often appear side by side. An API provides the contract. The coordination layer ensures messages move reliably between services. Treating them as interchangeable tools usually leads to fragile designs and duplicated logic.

Not Only for Large Enterprises

Another myth suggests only massive enterprises need this technology. That assumption no longer holds. Even mid-sized SaaS platforms and fast-growing startups benefit from a structured communication backbone.

As soon as multiple services, queues, or external integrations enter the picture, centralized coordination starts paying off. Smaller teams often adopt lightweight implementations early to avoid painful refactors later.

Performance Overhead Myth

Some engineers worry that adding a middle layer automatically slows systems down. In practice, the opposite often happens when the architecture is well planned.

Smart routing, connection pooling, and asynchronous messaging can reduce bottlenecks. Performance problems usually come from poor configuration, not from the concept itself. With proper tuning, the integration layer often improves overall system stability and throughput.

Best Practices for Implementing Middleware

Successful teams treat middleware as core infrastructure, not as an afterthought. Careful planning and disciplined operations make the difference between a clean architecture and a maintenance headache.

Start by choosing the right architectural style. Message-driven systems, request-response flows, and event streaming each require different design choices. Align the toolset with real workload patterns instead of following trends.

Performance monitoring should come early, not after problems appear. Track latency, queue depth, and error rates from day one. Early visibility prevents small issues from turning into production incidents.

Security also deserves strong attention. Enforce authentication, validate tokens, and encrypt sensitive traffic. Centralized policy enforcement is one of the biggest advantages of a well-designed integration layer.

Scalability planning matters just as much. Build with horizontal growth in mind so traffic spikes do not require emergency redesigns. Finally, avoid tight coupling between services. Loose boundaries keep systems flexible as requirements evolve.

Middleware vs Other Software Types

The term middleware sometimes overlaps with other software categories, which creates confusion for newcomers.

Quick comparison:

- System Software: Manages hardware and core operating functions. Examples include operating systems and device drivers. The integration layer sits above this level.

- Application Software: Focuses on user-facing functionality such as web apps or mobile tools. The coordination layer works behind the scenes to support those apps.

- Programming Software: Includes compilers, debuggers, and development frameworks used to build applications. Integration tools operate at runtime, not during code compilation.

- Embedded Software: Runs inside dedicated devices with fixed functions. Some embedded platforms use lightweight communication layers, but many do not require full-scale coordination infrastructure.

Conclusion

Modern platforms rarely succeed with direct, hard-wired connections between services. As systems expand across clouds and regions, middleware provides the structured communication backbone that keeps everything operating smoothly.

Used correctly, it reduces integration complexity, strengthens security, and supports long-term scalability. Teams gain cleaner service boundaries and fewer production surprises.

Looking ahead, the role of the integration layer will only grow as event-driven systems, microservices, and multi-cloud deployments continue to expand. Organizations that design with this reality in mind position their platforms for far more predictable growth.

FAQs About Middleware

What is middleware in simple terms?

It is software that sits between applications and helps them communicate, exchange data, and coordinate tasks reliably.

Is middleware the same as an API?

No. An API defines how a service is accessed. Middleware manages communication, routing, and coordination across multiple services.

Where is middleware commonly used?

It appears in distributed systems, microservices platforms, cloud applications, and enterprise integration environments.

Do small applications need middleware?

Not always. Simple apps with only a few services can often rely on direct API calls. Complexity usually determines the need.

Is middleware still relevant in cloud computing?

Yes. Cloud-native systems still require structured communication, especially when services scale dynamically across regions.