The modern digital landscape runs on data, and Storage Devices sit at the center of that transformation. Every photo captured, document created, and video streamed adds to the massive volume of information generated each day. What once measured in megabytes now grows into terabytes and beyond, driven by rapid advances in data-driven technology.

Personal gadgets and enterprise systems alike now store far more information than earlier generations ever handled. Smartphones keep thousands of photos, laptops manage large application libraries, and cloud platforms archive enormous datasets. This surge has pushed digital storage systems to evolve quickly in both capacity and speed.

Computer data storage is no longer a background feature. It has become a core requirement for performance, reliability, and user experience. Efficient methods for storing digital data allow applications to launch quickly, files to remain accessible, and operating systems to function smoothly.

What Are Storage Devices?

At the most basic level, Storage Devices refer to hardware components designed to retain digital information for later use. They preserve operating systems, applications, and user files so that computers can restart and continue functioning without losing important data.

Without reliable storage, a computer would behave like a blank slate every time it powered off. Educational sources such as GeeksforGeeks emphasize that systems rely on persistent storage to keep both the operating system and user data intact after shutdown. In practical terms, this means your files, settings, and installed programs remain available the next time the device starts.

Modern computing depends on this capability. From personal laptops to enterprise servers, machines must maintain information continuously. That responsibility falls squarely on Storage Devices, which act as the long-term memory of digital systems.

Storage Devices Within Computer Architecture

Inside a computer, storage works closely with several internal hardware components. The CPU processes instructions, RAM handles temporary working data, and the motherboard connects everything together. Storage hardware complements these elements by providing durable data persistence.

This relationship forms the backbone of efficient computer operation. When computer software launches, the processor retrieves information from the information storage system and loads necessary data into memory. Once processing completes, updated information often returns to the storage medium for safekeeping.

A key concept here is non-volatile storage. Unlike volatile memory, which loses data when power disappears, non-volatile solutions retain information even when the device is turned off. This persistence is what allows operating systems, applications, and personal files to survive across reboots.

Because of this role, storage hardware ranks among the most critical data storage hardware categories in modern machines. Without it, systems could process instructions temporarily but would fail to maintain long-term functionality. Reliable retention ensures continuity, stability, and user confidence across everyday computing tasks.

Types of Storage Devices

Modern computers rely on several categories of Storage Devices, each designed for a specific role within the broader data management ecosystem. Rather than viewing storage as a single component, it helps to think in layers that balance speed, capacity, and long-term reliability.

This section provides a high-level overview of the main types of storage devices used today. Detailed technical comparisons appear later in the article. For now, the goal is to build a clear mental map of how different storage tiers fit together.

Primary Storage Devices

Primary storage sits closest to the processor and focuses on speed rather than permanence. It temporarily holds data the system is actively using.

Key characteristics include:

- RAM (Random Access Memory): Acts as fast working memory that supports active programs and system operations.

- Cache memory: Located near the CPU, it stores frequently accessed instructions to reduce delays.

- Volatile behavior: Data disappears when power turns off, making this layer unsuitable for long-term retention.

- Temporary data handling: Optimized for rapid access during live computing sessions.

Primary storage plays a crucial role in overall responsiveness. Even though it does not permanently save files, it enables smooth real-time processing.

Secondary Storage Devices

Secondary storage provides persistent data storage for operating systems, applications, and personal files. This category forms the backbone of most computer data storage environments.

Important examples include:

- Hard Disk Drive (HDD): Uses magnetic recording to store large volumes of data at relatively low cost.

- Solid State Drive (SSD): Uses flash memory to deliver faster access speeds and improved durability.

- Persistent data storage: Retains information even when the computer shuts down.

This layer balances capacity and reliability, making it the primary long-term repository in most personal and business machines. Among all Storage Devices, secondary solutions typically hold the largest share of user data.

Tertiary and Archival Storage

Beyond everyday storage tiers, organizations often rely on archival storage for long-term preservation. This category focuses on durability and cost efficiency rather than immediate speed.

Common elements include:

- Tape storage systems: Widely used in enterprise environments for large-scale backups.

- Long-term backup systems: Designed to preserve information for years or even decades.

- Archival storage strategy: Optimized for infrequent access but maximum data durability.

These solutions play a critical role in disaster recovery planning and regulatory compliance, especially in large data environments.

Cloud-Based Storage Solutions

Cloud storage has transformed how individuals and businesses manage information. Instead of relying solely on local hardware, many organizations now store data across internet-based infrastructure.

Key characteristics include:

- Remote storage access: Files remain available from virtually any connected device.

- Internet-based data infrastructure: Large distributed systems manage replication and availability.

- Scalable cloud storage capacity: Users can expand storage without installing new physical hardware.

Cloud storage complements traditional Storage Devices by adding flexibility and geographic redundancy. It has become a major pillar of modern digital storage systems, particularly for collaboration, backup, and large-scale data management.

This layered view of storage technology helps readers see how different solutions cooperate rather than compete. Each tier serves a distinct purpose, and together they form the foundation that keeps modern computing reliable and efficient.

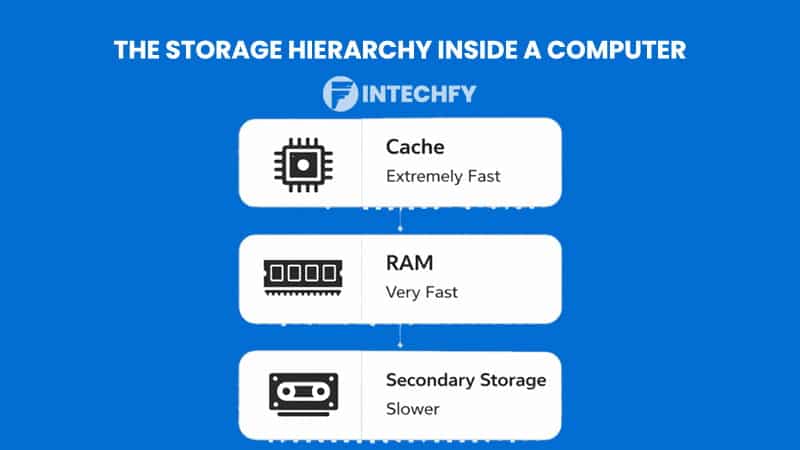

The Storage Hierarchy Inside a Computer

Modern computers rely on a carefully organized storage hierarchy to balance speed, capacity, and reliability. Instead of relying on a single memory layer, systems distribute data across multiple tiers that serve different purposes. This layered design ensures the processor always receives information quickly while still maintaining long-term data retention.

Within this hierarchy, Storage Devices work alongside volatile memory to create a smooth computing experience. RAM does not operate in isolation. It functions as part of a broader pipeline that moves information between high-speed memory and long-term storage. Each level in the storage hierarchy plays a distinct role, and performance depends heavily on how well these layers cooperate.

At the top sit the fastest memory components. Lower layers trade speed for larger capacity and persistence. This structured approach helps modern systems deliver both responsiveness and reliability without excessive cost or power consumption.

High-Speed Layer (Cache and RAM)

The high-speed layer focuses on immediate data access. It supports active programs and keeps the processor supplied with the information it needs at any given moment.

Key characteristics include:

- Volatile storage behavior: Data stored in this layer disappears when power is removed, which is why it is best suited for temporary workloads.

- Temporary data handling: RAM and cache manage live application data, system instructions, and frequently accessed resources.

- Extremely fast access times: These components operate far quicker than long-term storage, allowing the system to respond instantly.

- Close proximity to the CPU: Cache memory sits nearest to the processor, while RAM provides a larger high-speed workspace.

Because this layer relies on volatile memory, it cannot replace long-term retention. Instead, it acts as a performance booster that keeps real-time operations running smoothly.

Persistent Layer (Secondary Storage)

Below the high-speed tier sits the persistent layer, where Storage Devices provide durable data retention. This level ensures that files, operating systems, and applications remain available even after shutdown.

Important elements include:

- Solid State Drives (SSD): Use flash memory to deliver fast access speeds with no moving parts.

- Hard Disk Drives (HDD): Use magnetic recording to store large amounts of data cost-effectively.

- Non-volatile behavior: Information remains intact when power is turned off.

- Large capacity focus: Designed to hold operating systems, applications, and user files.

This layer represents the long-term memory of modern computers. While slower than RAM, it provides the persistence required for reliable everyday use.

Why Hierarchy Matters for Speed and Efficiency

The primary vs secondary storage relationship becomes clearer when viewed through performance needs. Fast memory alone would be too expensive at large scale, while relying only on long-term storage would slow systems dramatically. The hierarchy solves this trade-off.

Before looking at the summary table, remember that each layer is optimized for a different balance of speed, cost, and durability. Together, they create a pipeline that keeps modern machines efficient.

| Layer | Type | Speed | Volatility | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Cache | Extremely Fast | Volatile | CPU Cache |

| Level 2 | RAM | Very Fast | Volatile | DDR5 RAM |

| Level 3 | Secondary Storage | Slower | Non-Volatile | SSD, HDD |

The table highlights how speed decreases as persistence increases. Cache and RAM deliver rapid access for active tasks, while Storage Devices at the secondary level provide dependable long-term retention.

This layered structure is essential for modern performance. Without it, systems would either become too slow or too expensive to operate efficiently.

How Storage Devices Work

To understand modern computing, it helps to examine how Storage Devices actually store and retrieve information. Behind every saved document or opened file lies a structured sequence that ensures data moves safely between memory and long-term storage.

At a high level, the process begins when a user or application requests data to be saved or retrieved. The operating system then prepares the information, and the storage controller manages the physical write or read operation. This pipeline forms the backbone of reliable digital storage.

Below is a simplified view of the typical process.

| Step | Process Stage | What Happens | Example Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Request Initiated | User/system requests save or retrieve | Click “Save” |

| 2 | Data Preparation | OS organizes data into blocks | File converted to binary |

| 3 | Write Operation | Data written to medium | Saved to SSD/HDD |

| 4 | Data Stored | Controller confirms write | File appears |

| 5 | Read Operation | Data retrieved to RAM | Reopen document |

Read and Write Operations

At the core of storage functionality are read and write operations. Writing occurs when the system converts files into structured data blocks and sends them to the storage medium. Reading performs the reverse, retrieving those blocks and loading them into memory for active use.

File systems play an important role here. They organize how data blocks are indexed, located, and retrieved efficiently. Without this structured interaction, even advanced storage hardware would struggle to manage large volumes of information.

A dedicated storage controller oversees these tasks. It ensures data integrity, manages error checking, and coordinates communication between the operating system and the physical medium.

Magnetic Recording vs Flash Memory

Different storage technologies rely on different physical methods. Magnetic storage, commonly used in HDDs, writes data by altering magnetic patterns on spinning platters. This method offers large capacity at relatively low cost.

Flash memory, widely used in SSDs, stores information electronically using non-volatile cells. It provides faster access speeds and improved durability since no mechanical parts are involved.

Both approaches serve important roles in modern computer data storage. Magnetic systems excel in capacity-focused environments, while flash-based solutions prioritize speed and responsiveness.

Example: Saving a File Step-by-Step

Imagine saving a document after editing it. The moment you click save, the operating system prepares the file and converts it into binary data blocks. The storage controller then directs those blocks to the appropriate location on the drive.

Once the write operation completes, the system confirms the data has been stored safely. Later, when you reopen the file, the read process retrieves the stored blocks and loads them into memory.

This entire sequence happens in fractions of a second, yet it demonstrates the precise coordination that keeps digital storage reliable.

The Evolution of Storage Devices

The history of Storage Devices reflects the broader evolution of computing itself. Early computers relied on bulky, slow, and expensive storage solutions that limited how much data systems could retain. Over time, advances in materials, electronics, and architecture transformed storage into a high-speed, high-capacity foundation for modern computing.

In the early mechanical era, storage focused primarily on capacity. Engineers prioritized ways to hold more information at a lower cost. As software became more demanding and users expected faster response times, the industry shifted toward performance-driven designs. This transition led to the rise of flash-based technology and dramatically improved disk performance.

Today’s systems often combine multiple storage approaches to balance speed, durability, and affordability. To appreciate how far technology has progressed, it helps to look closely at the two most influential milestones: the hard disk drive and the solid state drive.

Hard Disk Drive (HDD): The Mechanical Storage Era

For decades, the hard disk drive served as the backbone of computer data retention. This technology uses spinning magnetic platters to record and retrieve information. Although newer solutions now dominate performance-focused systems, HDDs remain widely used due to their affordability and large capacity.

Key characteristics include:

- Magnetic platters: Data is written onto rotating disks coated with magnetic material, enabling large-volume storage.

- Moving parts: Mechanical arms and spinning disks handle read and write operations, which introduces physical wear over time.

- Cost per GB advantage: HDDs typically offer lower cost per gigabyte compared to newer flash-based alternatives.

Because of these traits, the hard disk drive became the default storage option for personal computers and servers for many years. However, mechanical limitations eventually created demand for faster and more durable alternatives.

Solid State Drive (SSD): Flash-Based Advancement

The introduction of the solid state drive marked a major turning point in the development of Storage Devices. Instead of relying on spinning disks, SSDs use NAND flash memory to store information electronically. This change removed many of the physical constraints associated with mechanical storage.

Important characteristics include:

- NAND flash technology: Stores data in non-volatile memory cells that retain information without power.

- No moving parts: Eliminates mechanical wear and reduces the risk of physical failure.

- Faster access speeds: Provides significantly improved read and write performance compared to traditional drives.

Industry analysis from IBM explains that HDD technology depends on magnetic media combined with mechanical motion, while SSDs rely on non-volatile flash memory with no moving components. This architectural shift is why SSDs generally deliver faster performance and improved energy efficiency.

The growing popularity of SSD technology has reshaped expectations around storage speed. Many modern systems now prioritize flash-based solutions, especially where responsiveness and reliability matter most.

HDD vs SSD Comparison

Before choosing between storage options, it helps to compare their core differences side by side.

| Feature | HDD | SSD |

|---|---|---|

| Storage Medium | Magnetic Platters | NAND Flash |

| Moving Parts | Yes | No |

| Speed | Moderate | High |

| Energy Use | Higher | Lower |

| Durability | Mechanical Wear | Shock Resistant |

This SSD vs HDD comparison highlights the trade-offs clearly. Mechanical drives still offer strong capacity at lower cost, while flash-based solutions dominate in speed and energy efficiency. Modern Storage Devices often combine both technologies depending on workload requirements.

Internal and External Storage Devices in Practical Use

In everyday computing, Storage Devices appear in both internal and external hardware forms. Each serves a practical purpose depending on how users manage their data. Rather than focusing on technical classification, it is more helpful to look at how these solutions function in real-world environments.

Internal Storage in Personal Computers

Internal drives form the primary data repository inside laptops and desktops. They store operating systems, installed applications, and personal files required for daily operation. Because they connect directly to the motherboard, internal solutions typically deliver faster data access time and more stable performance.

Most personal computers now use solid state drives as the main internal storage, though hard disk drives still appear in capacity-focused systems. The choice often depends on budget, speed requirements, and workload demands.

External Storage for Backup and Portability

External storage devices provide flexibility that internal drives cannot offer. Users commonly rely on portable storage solutions for backups, file transfers, and additional capacity. These devices connect through USB or other high-speed interfaces, making them easy to use across multiple systems.

Backup systems frequently depend on external drives to protect important data from hardware failure or accidental deletion. For students and professionals alike, portable storage remains a practical way to move large files between locations without relying entirely on cloud services.

Real Use Cases in Education and Business

Educational institutions often use external drives to distribute course materials, archive research data, and maintain secure backups. In business environments, companies deploy layered storage strategies that combine internal performance drives with external redundancy solutions.

This hybrid approach improves reliability while maintaining flexibility. As data volumes continue to grow, organizations increasingly rely on multiple Storage Devices working together to ensure both accessibility and protection.

How Storage Devices Influence System Performance

Beyond simple data retention, Storage Devices play a major role in overall system responsiveness. The speed at which a computer boots, loads applications, and handles large files often depends more on storage performance than raw processor power.

Boot Speed and Application Load Time

When a computer starts, the operating system must be read from storage into memory. Faster drives dramatically reduce boot time and improve the overall user experience. Systems equipped with modern SSDs often start in seconds, while older mechanical drives may take significantly longer.

Application launch speed follows the same principle. Programs stored on high-speed media load more quickly, which reduces waiting time during everyday workflows.

Impact on Gaming and Content Creation

Gaming and creative workloads place heavy demands on disk performance. Large game environments, video editing projects, and high-resolution assets require rapid data access. Slow storage can create noticeable delays, stuttering, or extended loading screens.

High-performance systems often pair fast processors with equally capable storage to avoid bottlenecks. Balanced hardware ensures smooth real-time performance across demanding applications.

NVMe and High-Speed Interfaces

The latest generation of NVMe storage pushes performance even further. By connecting directly through high-bandwidth interfaces, NVMe drives significantly reduce data access time compared to older SATA-based solutions.

This advancement has elevated expectations for modern Storage Devices, particularly in gaming rigs, professional workstations, and enterprise environments. Faster interfaces continue to reshape what users consider normal system responsiveness.

As storage technology evolves, its influence on computing performance will only grow stronger. Efficient data movement remains one of the most critical factors in delivering a smooth and reliable digital experience.

Storage Devices in Enterprise and Cloud Environments

In large-scale computing environments, Storage Devices play a far more strategic role than in personal systems. Enterprises must manage massive volumes of information while maintaining speed, availability, and data integrity. This requirement has driven the development of highly specialized enterprise storage solutions designed for reliability and scale.

Data Centers and Enterprise Architecture

Modern data centers rely on layered data center storage architectures that combine performance drives, high-capacity arrays, and redundancy mechanisms. Instead of using a single disk, organizations deploy clustered storage pools that distribute workloads efficiently.

Enterprise environments prioritize uptime and consistency. Systems often include redundant controllers, automated failover, and continuous monitoring to ensure data remains accessible even during hardware issues. This level of engineering helps businesses maintain operations without interruption.

The architecture also supports workload segmentation. Critical databases, analytics platforms, and user applications may each run on separate storage tiers optimized for their specific performance needs.

Cloud Storage Infrastructure

Cloud storage systems extend this concept even further by distributing data across geographically separated facilities. Instead of storing files on a single machine, providers replicate information across multiple nodes to improve availability and fault tolerance.

This distributed model allows organizations to scale quickly without purchasing additional physical hardware. It also supports remote collaboration, automated backups, and global content delivery. For many companies, cloud-based Storage Devices have become essential infrastructure rather than optional tools.

Security and redundancy remain central priorities. Cloud platforms typically include encryption, version control, and automated replication to reduce the risk of data loss.

Scalability and Big Data Growth

The rapid expansion of big data continues to reshape enterprise storage strategy. Businesses now collect information from sensors, transactions, user behavior, and analytics pipelines at unprecedented scale.

To handle this growth, storage platforms must expand without disrupting operations. Scalable architectures allow organizations to add capacity incrementally while maintaining consistent performance. As data volumes rise, flexible storage design becomes a competitive advantage.

Security, Reliability, and Lifespan of Storage Devices

Beyond capacity and speed, Storage Devices must protect information over time. Reliability and security directly affect whether data remains usable months or years after it is written. For both individuals and enterprises, strong data durability is just as important as performance.

Data Protection and Encryption

Modern systems rely heavily on encryption to safeguard sensitive information. Whether data sits on a local drive or inside cloud storage systems, encryption prevents unauthorized access if hardware is lost or compromised.

Access controls and authentication layers add another level of defense. Together, these mechanisms improve storage reliability by reducing the risk of data breaches and accidental exposure.

Lifespan of HDD vs SSD

Different storage technologies age in different ways. Mechanical drives experience wear due to moving parts, which can eventually lead to failure after extended use. Flash-based drives avoid mechanical wear but have finite write cycles that gradually reduce available memory cells.

In practical use, both technologies can last many years when properly managed. Monitoring tools help track drive health, allowing users to replace hardware before failures occur. Choosing the right device often depends on workload patterns and expected usage intensity.

Backup and Redundancy Strategies

No storage solution is completely immune to failure. For that reason, effective data backup systems remain essential. Organizations often follow the “3-2-1” approach: multiple copies of data stored on different media, with at least one copy kept offsite.

Redundancy technologies such as RAID arrays and cloud replication further improve data durability. These strategies ensure that even if one drive fails, critical information remains recoverable. Reliable protection depends on planning, not just hardware quality.

Storage Devices vs Processing Devices

Within any computer system, Storage Devices and processors serve different but tightly connected purposes. Storage hardware focuses on preserving information, while processing devices execute instructions and transform data into useful results.

This relationship forms the foundation of efficient computing. When an application launches, the processor retrieves program files from storage and loads them into memory. After execution, updated data often returns to the storage layer for safekeeping.

Neither component can function effectively alone. Without storage, systems would lose data after shutdown. Without processing hardware, stored information would remain inactive and unusable. Together, they create the hardware synergy that powers modern computing environments.

Conclusion

As digital ecosystems continue expanding, Storage Devices remain a cornerstone of reliable computing. They preserve operating systems, safeguard user files, and support the massive data flows that define modern technology.

From personal laptops to global cloud platforms, effective storage architecture ensures information stays accessible and secure. Advances in flash memory, distributed infrastructure, and high-speed interfaces continue pushing performance forward.

Looking ahead, demand for faster, larger, and more energy-efficient storage will only increase. Systems that manage data intelligently will shape the next generation of computing experiences.

FAQs About Storage Devices of Computer

What are the main types of storage devices?

The primary categories include primary storage (such as RAM and cache), secondary storage (HDD and SSD), archival systems, and cloud-based Storage Devices.

Is SSD always better than HDD?

Not always. SSDs offer faster speed and durability, while HDDs still provide better cost per gigabyte for large-capacity needs.

Are storage devices the same as memory?

No. Memory handles temporary working data, while storage hardware preserves information long term.

What storage is best for gaming?

High-speed SSD or NVMe drives typically deliver the best gaming experience due to faster loading times.

How long do storage devices last?

Most modern drives last several years under normal use, though lifespan varies based on workload, environment, and maintenance practices.