Modern computing is often associated with cloud platforms, artificial intelligence, and mobile-first technologies. Businesses today rely on distributed infrastructure to deliver services instantly, handle data at scale, and stay connected across borders. In large organizations, however, much of that activity still depends on a mainframe computer operating quietly behind the scenes.

From online payments to global logistics, digital operations now move at remarkable speed. Most users never see the systems processing those interactions, yet accuracy and continuity remain essential. When transactions involve money, identity, or national records, even a brief disruption can have serious consequences.

Because of that, many enterprises rely on large-scale systems built for stability rather than experimentation. These platforms are designed to run continuously, manage enormous workloads, and maintain consistency across millions of operations. This approach has shaped how enterprise computing functions for decades.

Despite this reality, mainframes are often viewed as outdated technology. The image that comes to mind is usually a massive machine locked inside an old data center, disconnected from modern innovation. That perception persists largely because these systems operate out of sight.

In practice, the opposite is often true. Global banks, airlines, and government institutions continue to depend on centralized platforms that prioritize reliability over rapid change. Many of these environments combine cloud services with long-established infrastructure to balance flexibility and control.

Rather than disappearing, the mainframe computer has adapted to modern demands. It now coexists with cloud platforms, supports high-volume digital services, and remains essential for mission-critical applications that cannot tolerate failure.

This quiet resilience explains why such systems continue to power a significant share of the world’s most important digital processes. To see why they remain relevant today, it helps to first understand what a mainframe actually is and how it was designed to operate within enterprise environments.

What Is a Mainframe Computer

A mainframe computer is a high-capacity computing platform built to handle extremely large volumes of data and transactions simultaneously. Unlike everyday computers designed for individual users, mainframes are created to support thousands — sometimes millions — of operations at the same time without interruption.

At its core, the system focuses on centralized processing. Instead of distributing workloads across many independent machines, tasks are managed from a single, tightly controlled environment. This approach allows organizations to maintain consistency, enforce security policies, and ensure predictable performance even during peak demand.

The primary function of a mainframe computer is not raw processing speed in the consumer sense. It is not designed to render graphics or run personal applications. Its strength lies in reliability, scalability, and sustained throughput. These machines are built to run continuously for years, often with scheduled downtime measured in minutes rather than hours.

Compared with personal computers and standard servers, the difference is philosophical as much as technical. PCs prioritize user interaction. Typical servers focus on flexible deployment. A mainframe system, by contrast, is optimized for long-term stability, massive input and output handling, and consistent performance under pressure. This is why industries that rely on uninterrupted service continue to invest in centralized computing models.

Mainframe Computer Definition in Simple Terms

In simple language, a mainframe computer is like the central brain of a large organization. Instead of many small devices making independent decisions, everything flows through one highly controlled core.

An easy analogy is a major international airport. Thousands of flights operate every day, but air traffic control coordinates everything from one central system. The goal is not speed for one plane, but safety and order for all of them together. Mainframes work in a similar way, prioritizing transaction processing over individual computing tasks.

Each operation — whether a bank transfer, airline booking, or payroll update — is handled accurately, recorded immediately, and verified before the next one proceeds. This focus on consistency explains why transaction processing, rather than computing power alone, defines the role of these systems.

Brief History of Mainframe Computers

The history of mainframe computers begins in the early days of digital technology, long before personal devices existed. During the 1950s and 1960s, organizations faced a growing need to automate calculations, record-keeping, and large data workloads. Early computers were expensive, enormous, and accessible only to governments and major corporations.

Early Mainframe Era

In this period, companies such as IBM emerged as pioneers. Early machines filled entire rooms and consumed significant electrical power. Processing was done primarily through batch jobs, where data was collected, submitted, and processed in large groups rather than instantly. Despite their limitations, these systems transformed accounting, census operations, and scientific research.

Reliability was already a priority. Even in its earliest form, the idea behind the mainframe computer was to provide stable processing for organizations that could not afford errors or downtime.

Transition to Enterprise Computing

As technology advanced through the 1970s and 1980s, systems evolved beyond simple batch processing. Real-time transaction handling became possible, allowing banks and airlines to update records instantly. This shift marked the true rise of enterprise computing.

During this era, many organizations built entire operations around what later became known as legacy systems. While the term “legacy” often implies obsolescence, in practice these platforms proved remarkably resilient. They handled growing workloads as businesses expanded globally, reinforcing trust in centralized architectures.

Modern Mainframe Evolution

The evolution of computing did not leave mainframes behind. Instead, they adapted. Modern platforms bear little resemblance to their early ancestors. Physical size shrank, performance increased dramatically, and virtualization became standard.

Today’s systems integrate encryption, advanced workload management, and connectivity with cloud environments. Rather than being replaced, they became part of hybrid architectures. This continuous adaptation explains why, despite decades of technological change, the mainframe computer remains deeply embedded in the infrastructure of modern enterprises.

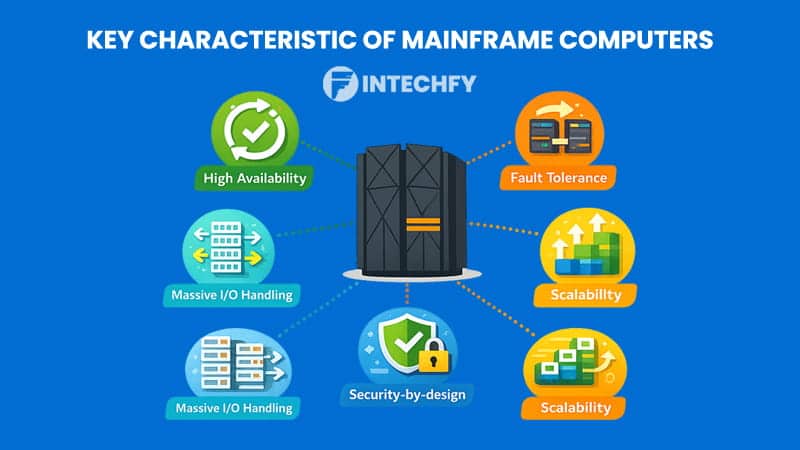

Key Characteristics of Mainframe Computers

What makes a mainframe fundamentally different is not its physical size or price, but the priorities behind its design. A mainframe computer is engineered to operate in environments where failure is unacceptable and interruptions can translate into massive financial or operational risk.

Instead of optimizing for flexibility or convenience, these systems are built around endurance, predictability, and long-term stability.

Unlike general-purpose machines, mainframes are expected to function continuously under heavy workloads. They must support thousands of users at once, process enormous volumes of data, and maintain accuracy even when demand spikes unexpectedly.

These requirements shape every layer of the platform, from hardware architecture to operating systems.

Reliability and High Availability

Reliability is the foundation of enterprise computing, and it is one area where the mainframe computer stands apart. These systems are designed for extremely high system uptime, often measured in years rather than days. Components such as processors, memory, and storage can be replaced while the system is running, allowing operations to continue without interruption.

This level of availability is supported by built-in fault tolerance. If one component fails, another immediately takes over without disrupting active workloads. For organizations handling financial settlements or national databases, this capability is not a luxury but a necessity.

Scalability and Performance

Scalability in mainframes follows a vertical model. Instead of adding more machines, organizations increase capacity within a single system. This approach allows performance to scale predictably while maintaining tight control over workloads.

A single mainframe computer can process massive volumes of input and output simultaneously. The focus is not raw speed for individual tasks, but sustained throughput across millions of transactions. This makes performance consistent even during peak activity, such as holiday retail periods or global market fluctuations.

Security and Data Integrity

Security is not added later in mainframe environments; it is embedded into the system’s core design. Access control, encryption, and auditing are tightly integrated at the hardware and operating-system levels.

This architecture protects data integrity by ensuring that every transaction is tracked, verified, and recoverable. For industries governed by strict compliance requirements, this built-in approach strengthens enterprise reliability and reduces exposure to breaches or data corruption.

Centralized Workload Management

Another defining feature is centralized workload management. Instead of competing for resources unpredictably, tasks are prioritized and scheduled according to business importance. Critical operations receive guaranteed resources, while lower-priority jobs are processed without interfering with essential functions.

This controlled environment allows organizations to maintain performance consistency even under extreme demand, reinforcing the system’s role as a dependable operational backbone.

How Mainframe Computers Work

Rather than focusing on individual applications, the system is designed to coordinate workloads across a shared environment where efficiency and control are tightly managed.

Mainframe Architecture Overview

At a high level, mainframe architecture is built around centralized processing supported by specialized subsystems. Input/output operations are handled independently from the main processors, reducing bottlenecks and improving efficiency.

This separation allows the system to manage thousands of concurrent tasks without slowing down. Data flows through structured channels, ensuring that heavy workloads do not overwhelm processing capacity.

Transaction Processing and OLTP

The core operational model revolves around transaction processing. In Online Transaction Processing (OLTP) environments, every action must be completed fully and accurately before the next one begins.

Whether processing payments or updating records, the system guarantees consistency. This is why a mainframe computer excels in environments where incomplete or duplicated transactions could cause serious consequences. Batch processing is also supported, allowing large volumes of data to be handled during scheduled windows without disrupting real-time operations.

Virtualization and Resource Allocation

Modern systems rely heavily on virtualization to maximize efficiency. A single physical machine can be divided into multiple logical environments, each running independently.

Resources are allocated dynamically based on workload demand. This enables precise workload management, allowing critical applications to receive priority while secondary processes run in the background. The result is a highly optimized environment that balances performance with control.

Through this architecture, the mainframe computer functions less like a traditional server and more like a self-contained computing ecosystem. Its ability to coordinate resources, enforce priorities, and maintain stability explains why it continues to support some of the world’s most demanding digital operations.

Mainframe Computer Operational Workflow

| Workflow Stage | What Happens | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Transaction Input | User actions such as payments, reservations, or data updates are submitted into the system through secure channels. | Ensures all operations enter the system in a controlled and traceable manner. |

| 2. Centralized Processing Control | The mainframe evaluates incoming requests and routes them through centralized processing logic. | Maintains consistency and prevents conflicting operations. |

| 3. Workload Classification | Tasks are categorized based on priority, such as real-time transactions or background batch jobs. | Allows critical operations to receive immediate attention. |

| 4. OLTP Execution | Each transaction is processed using OLTP rules, completing fully before the next step begins. | Guarantees accuracy and prevents partial or duplicated records. |

| 5. I/O Subsystem Handling | Input and output operations are processed by dedicated subsystems rather than the main processors. | Reduces performance bottlenecks and supports high-volume activity. |

| 6. Virtualized Resource Allocation | System resources are dynamically distributed across logical partitions based on demand. | Enables efficient use of hardware without sacrificing stability. |

| 7. Data Validation and Logging | Every completed transaction is verified, recorded, and logged for auditing. | Strengthens data integrity and compliance requirements. |

| 8. Continuous Monitoring and Adjustment | The system monitors performance and adjusts workload priorities in real time. | Maintains stability even during peak usage periods. |

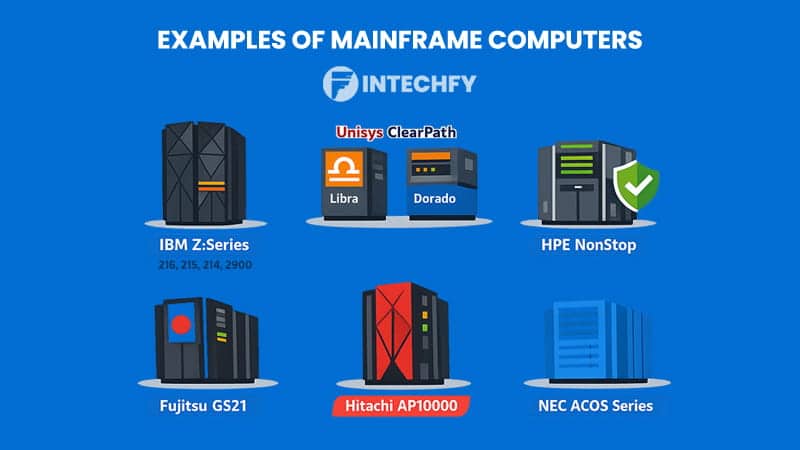

Examples of Mainframe Computers

These systems are not experimental or transitional technologies. They are mature, continuously developed environments trusted to support operations that cannot afford disruption. Each example reflects how the mainframe computer has evolved while maintaining its original purpose.

IBM Z Series / System z

IBM remains the most recognizable name in the mainframe landscape. Its Z Series, including models such as z14, z15, and the newer z16, represents the most widely deployed enterprise platform of its kind. These systems are used by major banks, insurance companies, and government institutions around the world.

What distinguishes IBM’s approach is its focus on integration rather than isolation. Modern Z systems are designed to operate alongside cloud platforms, encryption engines, and AI-driven analytics. A single mainframe computer in this family can process enormous transaction volumes while maintaining consistent performance across diverse workloads. This balance between legacy stability and modern adaptability is a key reason IBM continues to dominate the market.

Unisys ClearPath Dorado and Libra

Unisys offers its ClearPath family as an alternative enterprise-grade solution. The Dorado and Libra platforms are commonly found in government agencies, transportation networks, and large service providers.

ClearPath systems emphasize long-term continuity. Many organizations rely on applications that have been refined over decades, and Unisys focuses on preserving that investment while enabling modernization. Rather than forcing full system replacement, ClearPath environments support gradual evolution, which is often more realistic for large institutions managing sensitive data.

HPE NonStop

HPE NonStop systems are known for their strong emphasis on availability. Originally developed for fault-tolerant computing, these platforms are commonly used in environments where downtime has immediate financial consequences.

Industries such as stock trading, telecommunications, and payment switching rely on NonStop systems to ensure continuous operation. While not always categorized identically, they serve a similar role as a mainframe computer by prioritizing nonstop transaction processing and operational resilience above all else.

Fujitsu GS21 / BS2000

In Japan and parts of Europe, Fujitsu’s GS21 and BS2000 platforms remain significant. These systems are widely used in government administration, utilities, and large corporate data centers.

Fujitsu has focused on compatibility and longevity, allowing organizations to modernize interfaces without rewriting core applications. This approach reflects a broader enterprise mindset: stability and predictability often matter more than adopting the newest architecture.

NEC ACOS Series

NEC’s ACOS series has a long history in public-sector and financial environments, particularly in Japan. These systems are built to handle structured workloads such as tax systems, population records, and financial clearing.

The design philosophy emphasizes consistency and centralized management. For institutions that must maintain data accuracy across massive populations, the reliability offered by a mainframe computer remains difficult to replace with distributed alternatives.

Hitachi AP10000-VOS3

Hitachi’s AP10000 platform, running the VOS3 operating system, is another example of regionally significant enterprise infrastructure. Often deployed in banking and large manufacturing environments, these systems focus on transaction stability and long-term support cycles.

While less visible globally, they demonstrate how mainframe-style computing continues to exist beyond a single vendor ecosystem. The persistence of multiple platforms reinforces the idea that this model serves real operational needs.

Common Uses and Applications of Mainframe Computers

The continued presence of mainframes is best explained by where they are used. These systems remain embedded in industries that depend on precision, continuity, and scale. In such environments, replacing proven infrastructure carries risks that often outweigh potential cost savings.

Banking

Banks rely heavily on centralized platforms to manage deposits, transfers, and account balances. Every transaction must be recorded accurately and instantly. In these environments, a mainframe computer supports the core banking layer where errors are unacceptable and consistency is mandatory.

Financial Services

Beyond traditional banking, financial services include trading systems, clearing houses, and payment processors. These operations depend on enterprise transactions that must be completed in strict sequence. High-volume financial systems benefit from platforms designed to manage enormous workloads without data inconsistency.

Airlines and Reservation Systems

Airline reservation platforms operate continuously across time zones. Seat availability, pricing, and ticketing must update in real time across multiple channels. These systems often rely on centralized infrastructure capable of handling simultaneous booking requests without conflict.

Government Infrastructure

Governments manage population data, taxation, social services, and national identification systems. These databases form mission-critical infrastructure where security, auditing, and long-term reliability are essential. Many agencies continue to depend on mainframe environments because of their proven stability and strong data integrity controls.

Large-Scale Retail and Logistics

Retailers and logistics providers operate complex supply chains involving inventory tracking, order processing, and distribution management. During peak seasons, transaction volume can increase dramatically. Mainframes support these environments by maintaining performance consistency during extreme demand.

According to industry data, modern mainframe systems handle around 90 percent of global credit card transactions and nearly 68 percent of the world’s production IT workloads, while representing only about 6 percent of total IT spending. This imbalance highlights why organizations continue to trust these platforms despite their smaller presence in overall budgets.

For many enterprises, the decision is not about modernization versus tradition. It is about protecting mission-critical infrastructure that underpins daily operations. In that context, the mainframe computer remains less a legacy artifact and more a strategic foundation.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Mainframe Computers

Any technology that has survived for decades deserves to be examined from both sides. Mainframes continue to power critical enterprise environments, but their strengths also come with clear trade-offs. Looking at both advantages and limitations helps explain why these systems remain deeply embedded in certain industries while being absent from others.

Advantages

One of the most defining strengths of a mainframe computer is its extremely high reliability. These systems are engineered to operate continuously, often achieving near-zero downtime. Hardware components can be replaced while the system remains active, ensuring operations continue even during maintenance.

Security is another major advantage. Enterprise-grade protection is built directly into the architecture, not layered on afterward. Encryption, access controls, and detailed auditing support environments where data integrity and compliance are mandatory.

Mainframes are also capable of massive transaction throughput. They are designed to process enormous volumes of activity simultaneously without degradation in performance. This makes them ideal for organizations managing millions of daily interactions.

Perhaps less visible, but equally important, is the very long system lifecycle. Many platforms remain in productive use for decades, evolving through upgrades rather than replacement. This longevity contributes significantly to enterprise stability and predictable operations.

Disadvantages

Despite their strengths, mainframes come with notable challenges. Acquisition and maintenance costs are high, especially compared with commodity servers or cloud-based alternatives. Licensing, hardware, and long-term support represent substantial investment.

Another limitation is the shrinking pool of skilled professionals. Specialized knowledge is required to manage these environments, and fewer engineers are trained in traditional mainframe disciplines today.

Operational complexity also plays a role. While highly stable, these systems require structured governance and careful planning. Changes cannot be made casually, which can slow experimentation or rapid deployment.

Advantages vs Disadvantages of Mainframe Computers

| Aspect | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Performance | Extremely high transaction throughput | Not optimized for small workloads |

| Reliability | Near-zero downtime | Expensive maintenance |

| Security | Built-in enterprise-grade protection | Requires specialized expertise |

| Scalability | Efficient vertical scaling | High upfront investment |

This balance explains why a mainframe computer is rarely chosen for flexibility or cost efficiency. Instead, it is selected when consistency, trust, and operational continuity matter most.

Mainframe vs Other Computing Systems

Computers can be categorized in different ways depending on their purpose, scale, and design. In practice, each category exists to solve a specific type of problem, from personal productivity to large-scale industrial processing.

Across the computing landscape, systems are commonly divided into several groups:

- Supercomputers: Built for extreme computational tasks such as scientific simulations, weather modeling, and advanced research. These systems prioritize raw processing speed rather than transaction accuracy.

- Minicomputers: Once widely used by mid-sized organizations, these machines served as early shared computing platforms before being gradually replaced by modern servers.

- Microcomputers: Designed for individual use, typically found in offices and homes, focusing on affordability and everyday productivity.

- Personal computers: A subset of microcomputers aimed at direct user interaction, supporting applications such as document editing, design, and communication.

- Servers: Created to deliver shared resources such as applications, databases, and storage across networks, often operating within distributed environments.

- Workstations: High-performance computers built for specialized professional tasks, including engineering, design, and data analysis.

- Embedded computers

Integrated into devices and machinery, performing dedicated functions within vehicles, appliances, and industrial systems. - Digital computers: The most common form of modern computing, operating using binary logic to process structured data.

- Analog and hybrid computers: Used in specialized scientific and industrial scenarios where continuous data representation is required.

Within this structure, the mainframe computer occupies a separate space. It is not designed for individual users or experimental workloads. Instead, it operates as a centralized platform optimized for consistency, scale, and long-term operational stability.

Mainframe Computers in the Present and Future

Instead, they operate as part of a broader technology ecosystem that combines stability with modern flexibility.

At present, their role can be seen clearly in several areas:

- Still central to enterprise IT operations: Core business functions such as payment processing, account management, and large-scale record keeping continue to rely on centralized platforms built for long-term consistency.

- Integrated with cloud platforms: Many organizations now connect their mainframe computer environments with public and private cloud services, allowing front-end applications to scale while core transactions remain protected.

- Hybrid computing models becoming standard: Rather than choosing between legacy and modern systems, enterprises increasingly adopt hybrid structures that combine both.

This shift reflects a broader pattern of digital transformation. Innovation no longer requires replacing everything at once. Instead, companies modernize gradually while preserving systems that already work reliably at scale.

According to IBM, modern systems such as the IBM z16 are capable of processing over one million transactions per second and up to 19 billion transactions per day, highlighting their continued relevance in high-volume enterprise environments. These figures demonstrate why mainframes remain essential where speed, accuracy, and continuity intersect.

Looking ahead, the future direction is not focused on disappearance, but adaptation. Key developments include:

- Hybrid cloud integration: Mainframes increasingly operate as anchors within hybrid cloud architectures, supporting secure back-end processing.

- AI and analytics acceleration: Advanced analytics and AI workloads are being brought closer to transactional data, reducing latency and improving insight.

- Modernization strategies rather than full replacement: Organizations focus on refactoring interfaces, improving accessibility, and extending system life rather than removing core platforms.

In this context, the future of mainframe computing is defined less by reinvention and more by evolution — adapting proven systems to meet modern expectations without sacrificing reliability.

Conclusion

For decades, the mainframe computer has been misunderstood as a technology frozen in time. In reality, it has continued to evolve quietly while supporting some of the world’s most important digital operations.

From global banking networks to government infrastructure, these systems remain deeply embedded in daily life. Their value lies not in novelty, but in trust — the ability to process enormous volumes of data accurately, securely, and without interruption.

Rather than being displaced by cloud platforms, mainframes have learned to coexist with them. Hybrid environments now allow organizations to innovate at the edges while preserving stability at the core.

This balance explains their continued relevance. The mainframe computer is not obsolete, nor is it competing for consumer attention. It exists for a different purpose entirely: maintaining the digital foundations that modern society depends on.

As enterprise technology continues to evolve, these systems are far more likely to adapt than disappear. Their role may change, interfaces may modernize, and integrations may expand, but their importance within global digital infrastructure is set to remain.

FAQs About Mainframe Computer

What is the simple definition of a mainframe computer?

It is a large-scale computing system designed to handle massive volumes of transactions reliably and continuously.

What is another name for a mainframe computer?

It is often referred to as an enterprise system or centralized computing platform.

What is the latest mainframe computer?

IBM’s z16 is currently one of the most advanced systems in active enterprise use.

Why is a mainframe not a personal computer?

Because it is designed for centralized processing across thousands of users, not for individual interaction.

Is a laptop a mainframe computer?

No. A laptop is built for personal tasks, while mainframes support large-scale, mission-critical operations.