Modern technology rarely announces itself. It works quietly in the background, embedded inside machines, systems, and devices that people rely on every day. From factory automation lines to household appliances, the embedded computer has become a silent enabler of efficiency, precision, and reliability.

Unlike personal computers that invite user interaction, these systems are designed to operate continuously, often without direct human input, while delivering predictable and repeatable outcomes.

The distinction between general-purpose computers and embedded solutions lies in intent. A laptop or desktop is built to handle a wide range of tasks, while an embedded system is created for a specific purpose.

In this context, an embedded computer is optimized for stability, real-time behavior, and long-term operation rather than flexibility or user customization. This design philosophy explains why embedded technologies dominate environments where failure is not an option, such as industrial control, medical devices, and transportation systems.

As industries adopt automation, Internet of Things platforms, and smart infrastructure, embedded computing has moved from a supporting role to a foundational one. Sensors, controllers, and connected devices all depend on tightly integrated computing units that can operate with limited power, memory, and processing resources.

These constraints are not weaknesses but deliberate design choices that allow systems to function reliably for years.

What Is an Embedded Computer?

At its core, an embedded computer is a specialized computing unit designed to perform a dedicated function within a larger mechanical or electronic system. Instead of serving as a standalone device, it operates as one component in a broader architecture, often hidden from the end user.

Technically, an embedded computer combines processing, memory, and input/output interfaces into a compact platform that executes predefined tasks. Practically, it is the “brain” inside devices such as industrial controllers, medical instruments, or network equipment.

Unlike general-purpose machines, it runs a fixed set of instructions tailored to a single application, ensuring consistent behavior under specific conditions.

Many people wonder what are embedded computers used for in real-world scenarios. The answer spans across industries: regulating temperature in HVAC systems, controlling robotic arms, monitoring patient vitals, or managing communication between networked devices.

In each case, the computing unit is tightly coupled with computer hardware components such as sensors and actuators, forming a complete embedded systems solution.

An embedded computer differs from a desktop or laptop in several fundamental ways. It operates with constrained resources, prioritizes real-time responsiveness, and often lacks a traditional user interface.

According to explanations commonly referenced in ScienceDirect Topics, such systems are integrated directly into physical products to execute specific control or monitoring functions while consuming minimal power and memory.

This integration ensures efficiency, reliability, and long operational lifecycles, especially in environments where maintenance access is limited.

Because of these characteristics, an embedded computer is not defined by speed or storage capacity, but by how effectively it fulfills its dedicated role within a larger system.

Embedded Computers History

The origins of embedded computing can be traced back to the early days of digital electronics, long before consumer computers became widespread. The first instances of an embedded computer appeared in the 1960s, driven largely by military and aerospace requirements.

Guidance systems, avionics, and missile control platforms required compact, reliable computing units capable of operating under extreme conditions.

During this period, computing resources were scarce and expensive, which forced engineers to design systems that performed only essential tasks. This constraint-based design laid the foundation for modern embedded principles, including efficiency, determinism, and long-term stability.

As semiconductor technology advanced, embedded processors became smaller, more affordable, and more powerful.

The evolution continued into industrial automation, where programmable controllers replaced mechanical relays and analog controls. Manufacturing plants adopted embedded solutions to improve precision, safety, and scalability.

Over time, these technologies expanded into consumer electronics, automotive systems, and medical equipment.

Research summaries from EBSCO Research Starters highlight how embedded systems history reflects broader technological shifts. From early aerospace applications to automotive engine control units and smart appliances, embedded computing adapted to changing demands while maintaining its core philosophy.

Today, an embedded computer is a standard component in everything from network routers to wearable devices.

This historical progression explains why embedded technologies are so deeply integrated into modern life. They evolved not as general-purpose machines, but as specialized tools shaped by real-world constraints and mission-critical requirements.

Embedded Computer vs Embedded System

The terms embedded computer and embedded system are frequently used interchangeably, leading to confusion among readers new to the topic. While they are closely related, they do not describe the same thing.

An embedded system refers to the complete combination of hardware, software, and peripherals designed to perform a specific function. Within that system, the embedded computer acts as the central processing unit that executes instructions and coordinates operations.

An embedded system includes sensors, communication interfaces, power management components, and application-specific software. The computing element is only one part, albeit the most critical one. In other words, the embedded computer provides intelligence, while the embedded system delivers functionality.

A common misconception is that any small computer qualifies as an embedded system. In reality, size alone does not define embedded architecture. Purpose, integration, and operational constraints are far more important.

An embedded computer may be compact, but its defining feature is its role as a dedicated controller within a larger system rather than a user-facing device.

By separating these concepts, users can better evaluate products and technologies. When discussing performance, architecture, or processing capability, the focus is on the embedded computer.

When evaluating reliability, application scope, or system behavior, the broader embedded system perspective becomes more relevant.

How Embedded Computers Work

An embedded computer operates as a purpose-built control unit designed to handle a narrowly defined set of tasks. Instead of running many applications at once, it focuses on one primary job and executes it repeatedly with consistent timing.

At the heart of its operation is a cpu, which may be implemented as a microcontroller or a microprocessor, depending on performance and complexity requirements. This processor executes instructions stored in non-volatile memory and responds to signals coming from the surrounding hardware.

The general working principle follows a simple but reliable pattern: input, processing, and output. Input data comes from sensors, switches, or external communication interfaces. These signals represent real-world conditions such as temperature, motion, voltage levels, or user commands.

Once received, the processing unit interprets the data, applies predefined logic, and decides what action to take. The resulting output may control motors, update displays, regulate power, or transmit data to another system.

In this loop-based model, an embedded computer continuously reacts to its environment rather than waiting for user-driven commands.

One defining characteristic of this approach is limited system resources. Memory capacity, processing power, and energy consumption are intentionally constrained. These limitations encourage efficient software design and predictable behavior.

Instead of multitasking like a desktop machine, the system prioritizes deterministic responses, ensuring that critical operations happen within strict timing windows. This is why an embedded computer is commonly used in industrial control, automation, and safety-critical applications where timing accuracy matters more than raw performance.

Workflow Table — How Embedded Computers Work

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Input | Sensors, buttons, or external signals |

| Processing | CPU/MCU processes instructions |

| Memory | Limited ROM/Flash and RAM |

| Output | Actuators, displays, or control signals |

| Feedback | Repeating loop based on system function |

Core Components

Every embedded platform is built around a small set of essential components. The most important is the computer cpu, which executes instructions and manages system timing. In many designs, this takes the form of a microcontroller that integrates processing, memory, and peripherals into a single chip.

More demanding applications may rely on microprocessors with external memory and support circuitry. Memory resources typically include non-volatile storage for firmware and volatile RAM for runtime data. Input/output peripherals connect the processor to sensors, communication buses, and actuators.

Together, these components allow the system to interact with the physical world while maintaining predictable performance across long operating periods.

Hardware–Software Integration

Tight coupling between hardware and software defines embedded design. Low-level embedded software directly interacts with registers, timers, and communication interfaces. Firmware initializes the system, configures peripherals, and ensures safe startup behavior.

Device drivers provide a controlled way for software to access hardware features. Depending on complexity, the system may run on bare-metal code or use embedded systems software such as a real-time operating system.

This integration ensures minimal overhead and precise timing, which are difficult to achieve in general-purpose computing environments.

Operating Environment

Embedded platforms often operate in harsh or specialized environments. Industrial installations expose hardware to vibration, temperature extremes, and electrical noise. Real-time constraints require the system to respond within defined deadlines, sometimes measured in microseconds.

Unlike office computers, these systems must remain operational around the clock without human supervision, making stability and fault tolerance essential design priorities.

Functionality

Functionality in embedded platforms is deliberately narrow. Each system is designed to perform a dedicated task and perform it continuously. There is little room for feature expansion or user-driven customization.

This focus simplifies validation, reduces failure points, and allows the system to meet strict reliability targets over long service lifetimes.

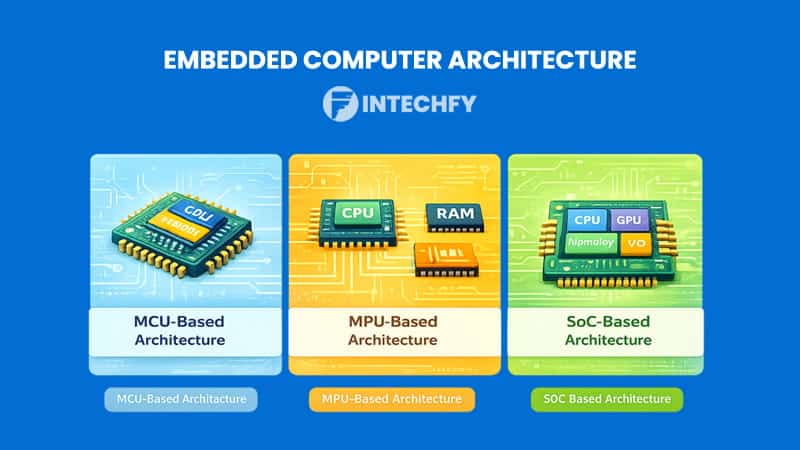

Embedded Computer Architecture

Architecture describes how processing, memory, and peripherals are organized within an embedded platform. The choice of architecture directly influences system performance, power consumption, scalability, and overall complexity.

Common embedded architecture approaches include:

- MCU-based architecture

Uses a single chip that integrates the processor core, memory, and I/O interfaces.- Low cost and minimal power consumption

- Compact physical footprint

- Well suited for simple control and monitoring applications

- MPU-based architecture

Relies on a standalone microprocessor connected to external memory and support components.- Higher processing capability

- Supports richer and more complex software environments

- Increased hardware and system design complexity

- SoC-based architecture

Integrates multiple processing cores, hardware accelerators, and peripherals on one chip.- Balances performance and energy efficiency

- Reduces board-level complexity

- Common in advanced industrial, multimedia, and connected systems

In each case, the embedded computer architecture reflects a deliberate trade-off between performance, power efficiency, and system complexity. Selecting the appropriate architecture ensures the system meets functional and reliability requirements without introducing unnecessary overhead or cost.

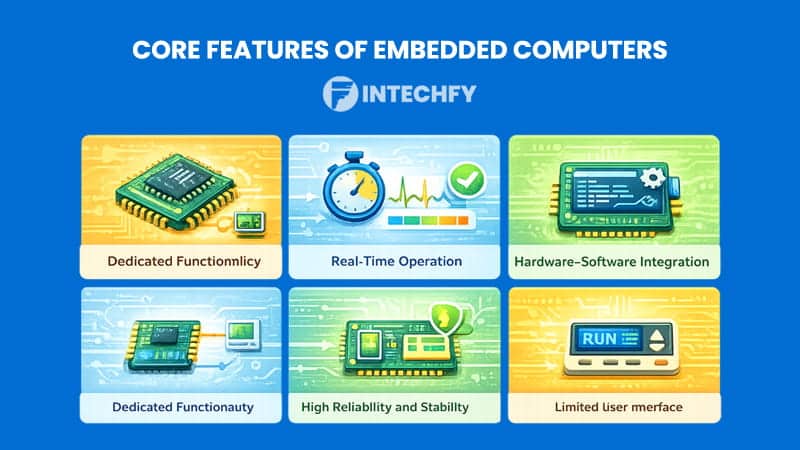

Core Features of Embedded Computers

Embedded computers are designed with a distinct set of characteristics that shape how they operate, interact with hardware, and respond to real-world conditions. These core features determine why they are widely used in systems that require consistent performance, long-term stability, and efficient resource usage.

Dedicated Functionality

Each system is designed for a specific purpose. This narrow focus allows designers to optimize performance and reliability without accommodating unrelated tasks or applications.

Real-Time Operation

Timely response is often critical. Real-time behavior ensures that operations occur within defined time limits, even under heavy load or continuous operation.

Hardware–Software Integration

Close coordination between code and hardware enables efficient resource usage. Software is written with full awareness of hardware constraints and capabilities.

High Reliability and Stability

Long operational lifecycles demand consistent behavior. An embedded computer is expected to run for years with minimal maintenance or downtime.

Compact and Low Power Consumption

Physical size and energy efficiency are key design goals. These systems are optimized to fit into constrained spaces and operate on limited power sources.

Limited User Interface

Most embedded platforms lack traditional keyboards or displays. Interaction is minimal and often indirect, reinforcing their role as background control units rather than user-facing devices.

Embedded Computer Software Stack

The software stack in embedded platforms is layered to maintain clarity and control. At the base lies firmware, which initializes hardware and establishes a known operational state. Above this layer, a real-time operating system may manage task scheduling, timing, and inter-process communication.

The application layer implements system-specific logic and decision-making. Throughout the stack, embedded software development emphasizes efficiency, predictability, and maintainability. Update and maintenance processes are carefully controlled, as changes can affect system stability.

In this environment, the embedded computer software stack prioritizes reliability over flexibility, ensuring consistent behavior throughout the product lifecycle.

Types of Embedded Computers

Embedded systems appear in many forms because their design is shaped by function, hardware capability, and physical deployment. Rather than following a single model, engineers classify them based on how they are expected to behave, how much processing power they require, and where they will operate.

By Functional Requirements

From a functional perspective, embedded systems are grouped by how they interact with their environment and how strict their timing requirements are.

Standalone Embedded Systems

These systems operate independently without relying on continuous network connectivity. They process input, perform logic, and generate output locally. Examples include washing machines, microwave controllers, and basic industrial controllers that handle fixed tasks without external coordination.

Real-Time Embedded Systems

Real-time systems are defined by timing constraints. Tasks must be completed within specific deadlines, not merely executed correctly. In hard real-time environments, missing a deadline can cause system failure, which is why this category is common in automotive control units, aerospace systems, and safety mechanisms.

Networked Embedded Systems

These systems communicate with other devices over wired or wireless networks. They exchange data, receive updates, and coordinate actions with remote platforms. Networked designs are common in industrial monitoring, building automation, and smart infrastructure.

Mobile Embedded Systems

Mobility introduces constraints related to power consumption, size, and wireless communication. These systems are designed to operate on batteries and handle intermittent connectivity. Wearable devices, portable diagnostic tools, and handheld terminals fall into this category. In all these cases, an embedded computer is tailored to meet specific functional demands rather than general-purpose use.

By Hardware and Processing Power

Hardware capability is another key dimension used to classify embedded designs. Processing requirements vary widely depending on application complexity.

Microcontroller-based Systems

These platforms integrate processing, memory, and peripherals into a single chip. They are efficient, low-cost, and widely used in control-oriented applications. Simple automation tasks, sensor nodes, and appliance controllers typically rely on this approach.

Microprocessor-based Systems

Microprocessor designs separate processing from memory and peripherals, allowing greater flexibility and performance. They support more complex operating systems and applications but require additional components. This category is common in multimedia devices, advanced industrial controllers, and communication equipment.

System-on-Chip (SoC)

SoC platforms combine multiple cores, accelerators, and interfaces into one integrated unit. They balance performance and energy efficiency while reducing board-level complexity. Many modern connected devices and edge computing platforms use this architecture.

Digital Signal Processors (DSPs)

DSP-based systems specialize in high-speed numerical processing. They are optimized for handling audio, video, and signal analysis tasks. Telecommunications equipment and real-time data processing applications often depend on this class of embedded computer to meet strict performance targets.

By Physical Form Factor and Application

Physical design and deployment environment also influence how embedded systems are categorized.

Single-Board Computers (SBCs)

SBCs integrate all essential components onto one board, simplifying development and deployment. They are commonly used for prototyping, education, and lightweight industrial applications where flexibility is required.

Industrial PCs (IPCs) and Rugged Systems

These systems are built to withstand harsh conditions such as vibration, dust, temperature extremes, and electrical noise. They are used in factories, transportation systems, and outdoor installations where standard consumer hardware would fail.

Panel PCs

Panel PCs combine computing hardware with an integrated display and touch interface. They are often mounted on machines or control cabinets, providing operators with direct access to system status and controls.

IoT Gateways

IoT gateways act as intermediaries between edge devices and cloud platforms. They collect data, perform local processing, and manage communication. In this role, an embedded computer must balance connectivity, security, and reliability within a compact form factor.

Embedded Computer Uses

The practical value of embedded systems becomes clear when examining how they are applied across industries. Each use case reflects specific operational demands and constraints that general-purpose computing cannot efficiently address.

Industrial Automation and Manufacturing

In manufacturing environments, embedded platforms control machinery, monitor production processes, and ensure consistent quality. They handle sensor input, coordinate actuators, and execute control algorithms in real time.

An embedded computer in this context is designed for continuous operation, high reliability, and resistance to industrial conditions such as dust, vibration, and electrical interference.

Automotive and Transportation

Modern vehicles rely on dozens of embedded systems to manage engine performance, braking, steering, and safety features. Transportation infrastructure also depends on these platforms for signaling, monitoring, and traffic control.

Here, deterministic timing and fault tolerance are critical, as system failures can directly affect safety.

Healthcare and Medical Devices

Medical equipment uses embedded technology to monitor patients, deliver therapy, and support diagnostics. These systems must comply with strict regulatory standards and operate with high accuracy.

An embedded computer in a medical device is engineered for precision, reliability, and long-term stability, often with limited user interaction.

Smart Home and Consumer Electronics

Smart appliances, home automation controllers, and entertainment devices rely on embedded platforms to provide responsive and intuitive functionality.

These systems integrate connectivity, user interfaces, and control logic while maintaining low power consumption and compact design.

IoT and Networking

In IoT deployments, embedded systems collect data from sensors, preprocess information, and manage communication with cloud services. They operate at the network edge, reducing latency and bandwidth usage.

An embedded computer used in this role must handle connectivity protocols, security functions, and local decision-making efficiently.

Retail and Logistics

Retail and logistics operations use embedded platforms for inventory tracking, point-of-sale systems, and warehouse automation.

These systems improve accuracy, streamline workflows, and enable real-time visibility across supply chains. Reliability and ease of integration are essential, as downtime directly impacts business operations.

Embedded Computer Advantages and Disadvantages

Evaluating an embedded platform requires looking at both its strengths and its limitations. These systems are not designed to replace general-purpose machines, but to solve specific problems efficiently and reliably.

Advantages

- High Efficiency & Performance: Embedded platforms are optimized for a defined task, which allows them to deliver consistent performance without unnecessary overhead. By running focused workloads, an embedded computer can achieve high efficiency even with modest processing resources.

- Low Power Consumption: Energy efficiency is a core design goal. Many systems operate on batteries or constrained power supplies, making low consumption essential. Hardware selection and software design work together to minimize energy use while maintaining functionality.

- Compact & Portable: Small physical size enables integration into devices where space is limited. From handheld tools to tightly packed industrial equipment, compact design allows deployment in environments unsuitable for larger machines.

- Cost-Effective: By eliminating unnecessary components and features, embedded solutions reduce manufacturing and operational costs. High-volume production further drives down unit prices, especially for consumer and industrial products.

- High Reliability & Stability

These systems are built for continuous operation over long periods. Limited functionality reduces failure points, allowing an embedded computer to operate for years with minimal maintenance. - Real-Time Operation: Deterministic timing ensures predictable responses. This capability is essential in applications where delayed actions can cause safety risks or system failure.

Disadvantages

- Difficult Upgrades and Modifications: Once deployed, changing hardware or software can be challenging. Updates may require physical access, specialized tools, or full system recertification.

- Limited Resources: Constraints on memory, processing power, and storage restrict application complexity. Developers must carefully optimize code to fit within these limits.

- Complex Troubleshooting: Diagnosing faults often requires specialized knowledge and debugging tools. Unlike personal computers, embedded platforms rarely provide detailed error feedback to users.

- High Development Cost: Although unit costs may be low, initial development can be expensive. Hardware design, testing, and validation demand significant time and expertise.

- Poor Connectivity or Interoperability: Some systems rely on proprietary interfaces or legacy protocols, limiting integration with newer platforms and services.

- Not User-Friendly: Minimal interfaces prioritize functionality over ease of use. This makes direct interaction difficult for non-technical users.

Challenges in Embedded Computer Development

Developing reliable embedded systems involves a distinct set of challenges that differ from traditional software or hardware projects. One major difficulty lies in debugging.

Limited interfaces and real-time constraints make it harder to observe system behavior during operation. Engineers often rely on specialized tools, simulators, and hardware probes to identify issues.

Hardware dependency is another challenge. Software is closely tied to specific processors, peripherals, and board layouts. A change in hardware can require substantial software rework, increasing development effort and risk.

This tight coupling means that portability is often limited compared to desktop or server environments.

Long lifecycle support further complicates development. An embedded computer may remain in service for a decade or more, outlasting the availability of original components and development tools.

Maintaining compatibility, applying security updates, and supporting aging hardware require careful planning from the outset. These challenges highlight why embedded development emphasizes thorough testing and conservative design choices.

Key Differences Between Embedded Computers and Other Types of Computers

Embedded platforms differ significantly from other computing models in purpose, design, and operation.

- Supercomputers: Built for massive parallel processing and scientific computation, unlike an embedded computer focused on single-task efficiency.

- Mainframe Computers: Designed for high-volume transaction processing, emphasizing throughput rather than real-time control.

- Minicomputers: Historically multi-user systems with broader functionality than embedded platforms.

- Microcomputers: General-purpose personal machines optimized for flexibility and user interaction.

- Server Computers: Built to manage network services and workloads for multiple clients simultaneously.

- Workstation Computers: High-performance desktops intended for professional applications.

- Personal Computers: Designed for versatility, software diversity, and direct user control.

- Digital Computers: Broad category encompassing most modern computing devices.

- Analog Computers: Use continuous signals rather than digital logic.

- Hybrid Computers: Combine digital and analog processing methods.

In contrast, an embedded computer is defined by its dedicated role, constrained resources, and close integration with hardware.

Conclusion

Embedded systems play a critical role in shaping modern technology by enabling machines, devices, and infrastructure to operate intelligently and autonomously. An embedded computer serves as the control core within these systems, executing specific tasks with high efficiency and reliability. Its importance lies not in versatility, but in precision, stability, and long-term operation.

As industries continue to adopt automation, connected devices, and smart systems, embedded platforms will remain foundational. From manufacturing and transportation to healthcare and consumer electronics, their use cases are defined by dedicated functionality and predictable behavior.

FAQs About Embedded Computers

What is meant by an embedded computer?

An embedded computer is a specialized computing unit integrated into a larger system to perform a dedicated function, often with limited resources.

What are examples of embedded computers?

Examples include industrial controllers, automotive control units, medical devices, routers, and smart appliances.

Is a laptop an embedded computer?

No. Laptops are general-purpose machines designed for flexibility and user interaction.

Is a TV an embedded computer?

Modern smart TVs contain embedded computing components that manage display, connectivity, and applications.

Which programming language is used for embedded systems?

Common languages include C, C++, and assembly, with higher-level options used in more complex systems.