Modern devices rarely operate on hardware alone. From smartphones to office laptops, computer software quietly directs how each system behaves and responds. Without it, even powerful machines would do nothing useful. Most people rely on digital tools every day, yet the layer that makes everything work often goes unnoticed.

Think about a normal work routine. Opening an operating system, launching productivity apps, or browsing the web all depend on tightly coordinated computer programs running behind the scenes. These invisible processes form what many professionals call digital software systems, turning raw hardware into something practical and responsive.

Clear software examples appear everywhere once you start paying attention. A browser renders web pages in milliseconds. A media player streams video smoothly. Messaging platforms deliver conversations in real time. Each tool focuses on a specific job, but together they create a seamless experience that feels simple on the surface.

What Is Computer Software

At its simplest level, computer software refers to the coded instructions that tell a machine what to do. Hardware provides the physical capability, but the decision-making logic comes from carefully written programs. Without those instructions, even advanced devices cannot complete meaningful tasks.

A practical software definition describes it as the logical layer of a computing environment. It converts human intent into machine-readable steps, allowing systems to process data, render interfaces, and automate routine work. These digital instructions are written in programming languages and organized into structured modules that the system can execute efficiently.

Inside a typical software system, executable programs are loaded into memory and run step by step. These programs manage everything from file access to user interaction. According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), software refers to computer programs and associated data that are stored in hardware and can be modified during execution. This view highlights how adaptable modern applications have become.

The connection between computer software and computer programs is extremely close. Individual programs handle specific tasks, while the broader environment coordinates how those tasks interact. Together, they create a layered structure capable of supporting everything from small utilities to large enterprise platforms.

To see the full picture, it helps to compare this logical layer with the physical components it depends on. The distinction becomes clearer when placed side by side with hardware.

Software vs Hardware

People often mix up digital instructions with the machines that run them. In practice, computer software and computer hardware play very different roles, even though they must operate together at all times.

Hardware refers to the physical system components you can touch, including processors, memory modules, and storage devices. Software exists as coded logic stored electronically. One provides the muscle, the other provides the direction. This constant hardware and software interaction is what allows modern systems to function smoothly.

Consider a simple scenario. A laptop CPU can process billions of operations every second, but without an operating system and applications, it has no clear task. The software layer gives the machine purpose, telling it how to respond to user input, manage files, and run services efficiently.

Software vs Hardware Comparison

| Aspect | Software | Hardware |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Intangible instructions | Physical components |

| Function | Controls system operations | Executes physical processing |

| Dependency | Requires hardware to run | Requires software to operate |

| Examples | Operating systems, applications | CPU, RAM, storage |

In everyday computing, computer software acts as the control center while hardware performs the physical work. Both layers depend heavily on each other, and neither delivers real value when operating alone.

Seeing how this partnership works makes troubleshooting far more straightforward. When a program fails, the issue often comes from the code rather than the device. When a system slows down, the limitation may come from constrained hardware resources instead of the application itself.

Even as technology keeps advancing, the core relationship between logical instructions and physical machines remains fundamentally the same.

Characteristics of Software

The overall quality of computer software is not judged by appearance alone. Engineers and product teams evaluate it through a set of measurable attributes that reflect how well the system performs in real use. In practice, key characteristics of computer software include functionality, reliability, usability, efficiency, maintainability, portability, security, and scalability.

Each attribute highlights a different strength. Together, they determine whether an application feels smooth, dependable, and ready for long-term use. High-quality computer software balances these factors rather than optimizing only one area. When developers ignore even one of these traits, the user experience usually suffers.

Key Characteristics of Computer Software

| Characteristic | What It Means | Why It Matters in Computer Software |

|---|---|---|

| Functionality | Ability to deliver required features | Ensures tasks are completed correctly |

| Reliability | Consistent performance over time | Builds user trust and stability |

| Usability | Ease of learning and operation | Improves productivity |

| Efficiency | Optimal resource usage | Prevents system slowdowns |

| Maintainability | Ease of updates and fixes | Supports long-term evolution |

| Portability | Ability to run across platforms | Increases flexibility |

| Security | Protection against unauthorized access | Safeguards data |

| Scalability | Ability to handle growth | Supports expanding workloads |

Functionality

Functionality focuses on whether the application actually delivers what users expect. Strong software performance comes from features that solve real problems instead of adding unnecessary complexity.

For example, a photo editing tool should export images accurately and apply filters correctly. If key features fail or behave inconsistently, users quickly lose confidence in the product.

Reliability

Reliability measures how stable a system remains over time. Users expect applications to run without frequent crashes, freezes, or unexpected errors. Good software reliability depends heavily on proper error handling and consistent testing.

A banking app illustrates this well. If transactions occasionally fail or display incorrect balances, trust disappears immediately. Long-term stability is what keeps users coming back.

Usability

Usability reflects how easy the computer software feels during everyday use. Clean navigation, clear labeling, and logical workflows all contribute to strong user interface software design.

A steep learning curve often pushes users away, even when the underlying features are powerful. Products that feel intuitive usually achieve higher user satisfaction and faster adoption.

Efficiency

Efficiency looks at how well an application uses system resources. Programs that consume excessive CPU power or memory often cause slowdowns across the entire device. Strong software efficiency keeps performance responsive without wasting resources.

Lightweight background utilities are a good example. When optimized properly, they run continuously without noticeable impact on system speed.

Maintainability

Maintainability determines how easily developers can update, debug, and improve the product over time. Projects built with clear structure and modular design tend to score high in software maintainability.

This characteristic becomes critical after launch. Software that is difficult to modify often accumulates technical debt, making future improvements slower and more expensive.

Portability

Portability refers to how well an application runs across different platforms or environments. Strong compatibility within a software environment allows teams to deploy the same product on multiple systems with minimal changes.

Cross-platform productivity apps demonstrate this benefit clearly. Users expect the same experience on Windows, macOS, and mobile devices without major differences.

Security

Security focuses on protecting systems and user data from unauthorized access. Effective software security combines authentication controls, encryption, and continuous monitoring.

Applications that handle sensitive information must treat this area seriously. Weak protection can expose personal data, damage brand reputation, and create legal risks.

Scalability

Scalability measures how well a system handles growth. As user demand increases, the application should maintain performance without major redesign. Strong computer software scalability allows platforms to expand smoothly.

Cloud-based services highlight this need. When traffic spikes suddenly, well-designed systems continue operating normally instead of slowing down or crashing.

How Software Works

Behind every application is a structured process that turns human-written code into machine activity. Computer software does not run instantly after being written. It moves through several technical stages before it can perform useful work.

Most modern systems follow a predictable execution path, starting with development and ending with hardware communication.

Software Execution Workflow

| Stage | What Happens | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Creation | Code written by developers | Source code |

| Translation | Compiler/interpreter converts | Machine code |

| Execution | Program runs in memory | Active process |

| Hardware Interaction | OS & drivers communicate | Completed task |

Creation

The process begins when developers write program instructions using programming languages such as Python, Java, or C++. These instructions describe exactly what the system should do step by step.

Modern software development tools help teams manage large codebases, track changes, and collaborate efficiently. At this stage, the program exists as human-readable source code and cannot yet run directly on hardware.

Translation

Next comes translation. During this phase, code compilation or an interpreter converts the human-readable program into machine code. This step is essential because processors only understand low-level binary instructions.

Compiled languages produce standalone executables, while interpreted environments translate instructions on the fly. Either way, the goal remains the same: transform developer logic into something the processor can execute.

Execution

Once translated, the computer software execution process begins. The operating system loads executable programs into memory and starts running them as active processes.

During execution, the application performs calculations, manages data, and responds to user input. Performance at this stage depends heavily on optimization and resource management.

Hardware Interaction

The final stage connects logic with physical components. Through hardware and software interaction, the operating system and device drivers translate program requests into electrical actions.

For example, when a user clicks “print,” the application sends instructions to device drivers, which then communicate with the printer hardware. This coordination allows computer software to produce real-world results from purely digital logic.

Even as platforms evolve, this layered workflow remains the backbone of modern computing systems.

Function of Software

The real value of computer software becomes clear when you look at what it actually does inside modern devices. Software is not just a collection of code. It manages systems, runs applications, processes information, and connects users with hardware in ways that feel almost effortless.

Without this digital layer, even powerful machines would struggle to perform basic tasks. Software creates structure, automation, and usability across every computing environment. From enterprise servers to personal laptops, its functions shape how technology behaves in daily use.

System Management

One of the most critical responsibilities is system management. Software coordinates memory usage, schedules processes, and ensures that hardware resources are shared efficiently.

Operating systems handle this behind the scenes, allowing multiple programs to run smoothly without constant user intervention.

Application Execution

Software also enables application programs to run correctly. When a user opens a browser, editor, or media player, the system loads and executes the required instructions.

This layer ensures user programs launch quickly, receive the resources they need, and close cleanly when tasks are complete.

Data Handling

Modern computing depends heavily on data processing software. Applications must store, retrieve, modify, and transmit information accurately and quickly.

Database systems, spreadsheets, and analytics tools all rely on structured data handling to keep operations reliable and organized.

User Interface

User interface software bridges the gap between humans and machines. Graphical layouts, menus, and interactive elements make complex systems feel approachable.

A well-designed interface reduces the learning curve and improves overall productivity across devices.

Security

computer software protection plays a major role in safeguarding systems and user data. Security features include authentication controls, encryption, and threat monitoring.

Strong protection mechanisms help prevent unauthorized access and reduce the risk of data breaches.

Hardware Control

Many systems depend on firmware software to communicate directly with physical components. This layer translates high-level instructions into signals that hardware can understand.

Device initialization, peripheral control, and low-level configuration all rely on this function.

Automation

Automation software reduces manual effort by allowing systems to perform repetitive tasks automatically. Scheduled backups, workflow triggers, and smart assistants all fall into this category.

Automation improves efficiency and allows users to focus on higher-value work instead of routine operations.

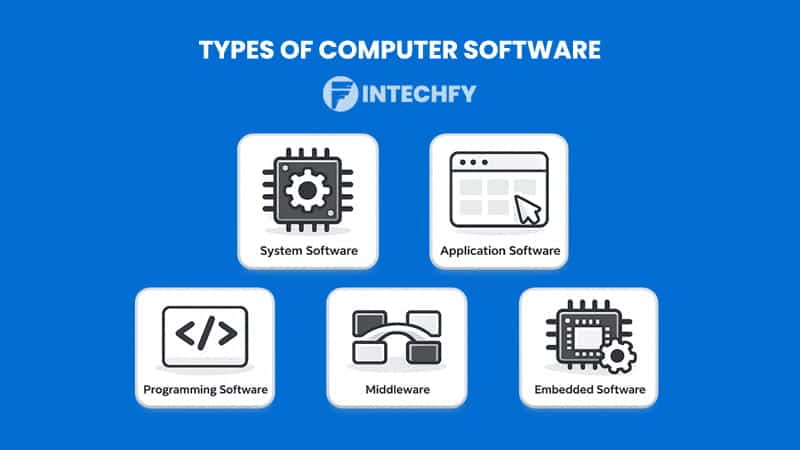

Types of Computer Software

Software comes in several major categories, each designed for a specific role within the computing ecosystem. Encyclopaedia Britannica notes that computer software is broadly divided into system software, which manages internal computer operations, and application software, which performs user-oriented tasks.

That broad distinction provides a useful starting point, but the modern landscape includes additional layers that support development, integration, and specialized device control. Understanding these categories helps users and developers choose the right tools for each situation.

System Software

System software forms the foundation that keeps devices running. It includes operating system software, utility programs, device drivers, and firmware software. Together, these components manage hardware resources and create the environment where other programs operate.

Operating systems such as Windows, Linux, and macOS coordinate memory, storage, and process scheduling. Utility programs handle maintenance tasks like disk cleanup, backups, and performance monitoring. Device drivers allow peripherals such as printers and graphics cards to communicate with the system correctly.

Firmware software operates at an even lower level. It initializes hardware during startup and provides basic control routines. Without this layer of computer software, most devices would fail to boot or function properly.

Application Software

Application software focuses on end-user productivity and everyday tasks. These software applications include word processors, web browsers, design tools, and media players. Unlike system-level tools, they are designed primarily for direct human interaction.

User programs help people write documents, edit photos, manage finances, and communicate online. Productivity suites, streaming platforms, and creative tools all fall into this category.

Because application tools sit closest to the user, their design strongly influences user satisfaction. Performance, interface clarity, and feature relevance all matter. In many environments, this category of computer software receives the most attention from everyday users.

Programming Software

Programming software supports developers who build and maintain applications. This category includes software development tools such as integrated development environments, compilers, debuggers, and advanced code editors.

These tools simplify the process of writing, testing, and optimizing code. Compilers convert human-readable programs into machine instructions. Debuggers help identify and fix errors. Code editors improve productivity with syntax highlighting and automation features.

While most end users never interact with this layer directly, it plays a crucial role in shaping the quality and reliability of modern computer software products.

Middleware

Middleware acts as a bridge between different systems or applications. Sitting in the middleware layer, it enables communication and data exchange across platforms that might otherwise remain isolated.

Large enterprise environments rely heavily on middleware to connect databases, web services, and distributed applications. Message queues, API gateways, and transaction managers are common examples.

By simplifying integration, middleware reduces complexity for developers and improves overall system coordination.

Embedded Software

Embedded systems software is designed to control dedicated devices rather than general-purpose computers. It operates inside products such as smart TVs, automotive systems, medical equipment, and IoT devices.

This type of software focuses on stability, efficiency, and tight hardware integration. Many embedded platforms also rely on firmware relationships to manage low-level operations.

Because embedded solutions often run continuously for long periods, reliability and resource efficiency become especially important.

Other Ways Software Is Classified

Beyond functional categories, computer software can also be grouped using several alternative classification methods. These approaches help organizations evaluate licensing models and potential security risks at a high level.

Based on Licensing

Software licensing determines how users can access, modify, and distribute a product. Common categories include:

- Freeware – available at no cost for general use.

- Shareware – distributed freely but often limited until purchased.

- Open source software – source code is publicly available for modification and redistribution.

- Proprietary software – owned and controlled by a specific company with restricted usage rights.

Each model affects cost, flexibility, and long-term support considerations.

Based on Security Risks

Software can also be categorized by potential threat behavior. At a high level, security-related classifications include:

- Malware – malicious programs designed to damage or disrupt systems.

- Spyware – tools that secretly collect user information.

- Ransomware – software that locks data until payment is made.

- Adware – programs that automatically display unwanted advertisements.

Recognizing these categories helps users stay alert and maintain safer computing environments.

Examples of Computer Software

Looking at real products makes the concept easier to grasp. Computer software appears in many forms across everyday devices, from core system tools to user-focused applications and developer utilities. Grouping common software examples helps clarify how each category supports different computing needs.

System Software Examples

System-level tools operate closest to the hardware layer and keep the device running smoothly. They manage resources, handle background operations, and ensure the system stays stable.

Common examples include:

- Operating systems such as Windows, Linux, and macOS

- Device drivers for printers, GPUs, and network adapters

- Utility tools like disk cleanup and antivirus scanners

- Firmware components that initialize hardware at startup

These foundational layers rarely attract attention, yet they are essential for maintaining a reliable computing environment.

Application Software Examples

Application software examples are far more visible because users interact with them directly. These computer applications are designed to help people complete specific tasks efficiently.

Typical examples include:

- Web browsers for accessing online content

- Office suites for documents, spreadsheets, and presentations

- Photo and video editing tools

- Streaming and media playback platforms

- Communication and meeting applications

Because these tools sit closest to the user experience, performance, usability, and interface design play a major role in their success.

Programming Tools

Programming tools support developers who create and maintain digital products. Unlike end-user apps, these tools focus on writing, testing, and optimizing code.

Widely used examples include:

- Integrated Development Environments (IDEs)

- Compilers that convert source code into machine code

- Debugging tools for identifying and fixing errors

- Code editors for writing and reviewing source files

- Testing frameworks that validate software behavior

Why Computer Software Is Important

The importance of computer software becomes obvious once you consider how deeply it shapes modern life. Nearly every digital activity, from sending messages to running global businesses, depends on software working reliably behind the scenes.

Productivity is one of the biggest benefits. Office tools, collaboration platforms, and specialized industry programs allow individuals and teams to complete work faster than ever. Tasks that once required hours of manual effort can now be finished in minutes with the right digital tools.

Automation also plays a major role. Scheduled backups, workflow triggers, and smart assistants reduce repetitive work and minimize human error. Businesses rely heavily on automation to maintain consistency while scaling operations. Without these capabilities, many processes would become slow and costly.

The digital economy runs on software-driven platforms. E-commerce systems, financial services, cloud platforms, and mobile ecosystems all depend on reliable code to function smoothly. As more industries shift online, the role of computer software continues to expand.

Device usability is another key factor. Well-designed interfaces make complex machines feel simple and approachable. When software is intuitive, users spend less time learning and more time getting real work done.

For both individuals and organizations, software is no longer optional infrastructure. It is the layer that transforms raw hardware into practical, productive technology.

Conclusion

Across modern computing, computer software acts as the quiet engine behind nearly every digital experience. It manages resources, runs applications, processes data, and connects users to hardware in ways that often go unnoticed.

From low-level system tools to user-facing applications and developer platforms, each layer plays a distinct role in the broader ecosystem. Strong design, consistent reliability, and solid security practices determine whether software feels smooth and dependable or frustrating and unstable. These fundamentals continue to matter as technology advances.

A clear grasp of how computer software operates gives users a practical edge. It becomes easier to choose the right tools, diagnose performance problems, and evaluate new platforms with confidence. Even a basic level of familiarity can make everyday computing far less confusing.

The importance of this digital layer will only grow. Cloud services, artificial intelligence, and connected devices all depend on increasingly capable code to function properly. As systems become more complex, well-built computer software remains the factor that keeps everything running efficiently.

Put simply, hardware supplies the raw power, while software provides the direction that turns modern devices into useful, productive tools.

FAQs About Computer Software

What is computer software in simple terms?

Computer software is a collection of programs and digital instructions that tell a computer how to perform specific tasks.

What are the main types of software?

The primary categories include system software, application software, programming tools, middleware, and embedded solutions.

What is the difference between software and hardware?

Software consists of intangible instructions and code, while hardware refers to the physical system components such as processors, memory, and storage.

Can a computer run without software?

No. Without software, hardware has no instructions to follow and cannot perform meaningful operations.

What are examples of system software?

Common examples include operating systems, device drivers, utility tools, and firmware that manage core system functions.